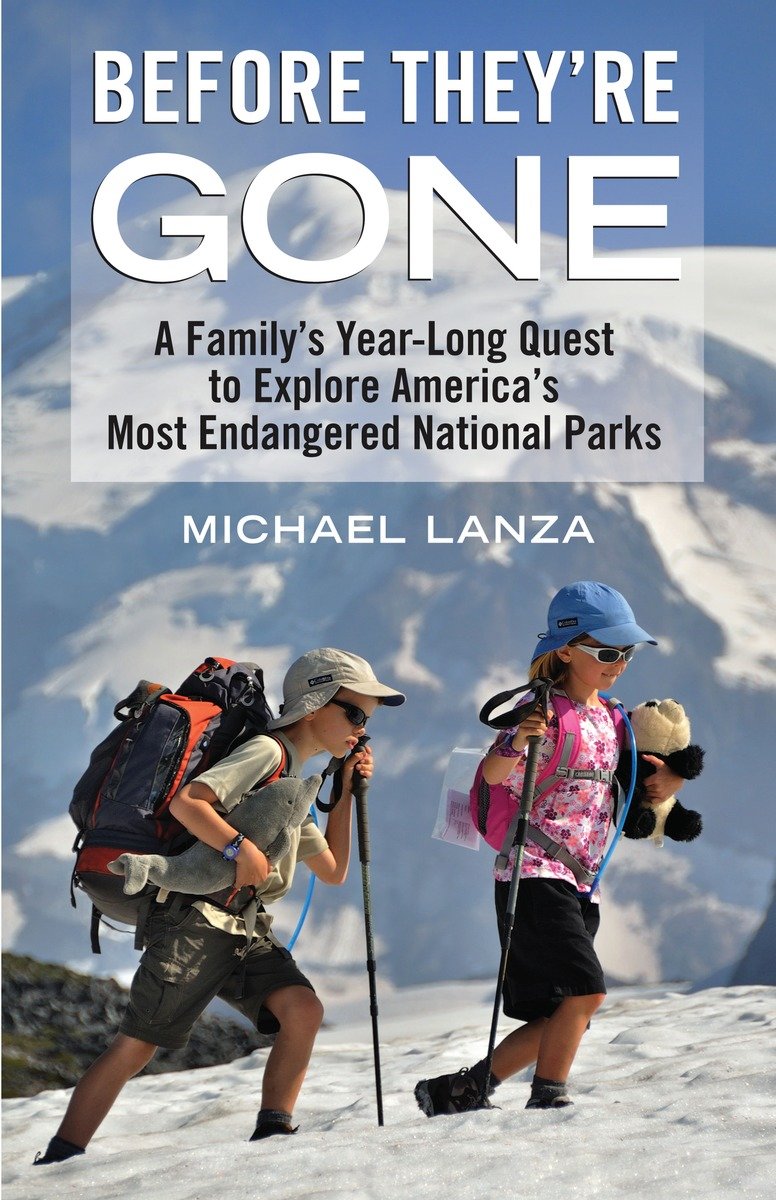

A Family’s Year-Long Quest to Explore America’s Most Endangered National Parks: Before They’re Gone

14.00 JOD

Please allow 2 – 5 weeks for delivery of this item

Description

A longtime backpacker, climber, and skier, Michael Lanza knows our national parks like the back of his hand. As a father, he hopes to share these special places with his two young children. But he has seen firsthand the changes wrought by the warming climate and understands what lies ahead: Alaska’s tidewater glaciers are rapidly retreating, and the abundant sea life in their shadow departs with them. Encroaching tides threaten beloved wilderness coasts like Washington’s Olympic and Florida’s Everglades. Less snowfall and hotter summers will diminish Yosemite’s world-famous waterfalls. And it is predicted that Glacier National Park’s 7,000-year-old glaciers will be gone in a decade. To Lanza, it feels like the house he grew up in is being looted. Painfully aware of the ecological—and spiritual—calamity that global warming will bring to our nation’s parks, Lanza sets out to show his children these wonders before they have changed forever. He takes his nine-year-old son, Nate, and seven-year-old daughter, Alex, on an ambitious journey to see as many climate-threatened wild places as he can fit into a year: backpacking in the Grand Canyon, Glacier, the North Cascades, Mount Rainier, Rocky Mountain, and along the wild Olympic coast; sea kayaking in Alaska’s Glacier Bay; hiking to Yosemite’s waterfalls; rock climbing in Joshua Tree National Park; cross-country skiing in Yellowstone; and canoeing in the Everglades. Through these poignant and humorous adventures, Lanza shares the beauty of each place and shows how his children connect with nature when given “unscripted” time. Ultimately, he writes, this is more their story than his, for whatever comes of our changing world, they are the ones who will live in it.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.29 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 1.43 × 14.05 × 21.62 cm |

| PubliCanadation City/Country | USA |

| by | |

| format | |

| Language | |

| Pages | 224 |

| publisher | |

| Year Published | 2013-4-9 |

| Imprint | |

| ISBN 10 | 0807001848 |

| About The Author | Michael Lanza is a veteran freelance outdoors writer and photographer. He is the northwest editor of Backpacker magazine, where his articles about the impacts of climate change on Montana’s Glacier National Park and other wild lands helped Backpacker win a National Magazine Award. He runs the website TheBigOutside. |

“A beautifully written, moving meditation.”—Richard Louv, author of The Nature Principle “Encounters with bears and alligators as well as tender parent-child moments . . . make [Before They’re Gone] an informative, heartwarming and, at times, heart-stopping read.” —Colleen McBrinn, The Today Show’s travel blog“The season’s must-read new memoir about bringing up adventure kids in the age of climate change.” —Outside Magazine’s Raising Rippers blog"This is a terrific blend of adventure…and ecological forecasting (and forewarning) that aptly conveys the passion of a devoted outdoorsman, and serves as a wake-up call to the state of our planet."—Publishers Weekly“Intriguing premise; decent execution—certainly of interest to environmentalists and other eco-minded readers.”—Kirkus Review “Michael Lanza braids a story of family, wilderness, and climate that's at once heartwarming and terrifying. I envy his kids for the incredible year they spent exploring America's finest wild places. And I mourn that they—and my own daughter—will have to endure the devastating consequences of our heating planet. Lanza makes abundantly clear that our children deserve better than the legacy we’re leaving them.”—John Harlin, author of The Eiger Obsession: Facing the Mountain that Killed My Father“I grew up in a national park, worked in twelve others and have visited well over two hundred of them. Their values, for people like me, often are taken for granted. In this wonderful book, Michael Lanza’s children learn and experience what is most important about our national parks – the necessity to leave them ‘unimpaired for future generations’ – and why.”—Bill Wade, Chair, Executive Council, Coalition of National Park Service Retirees and former superintendent of Shenandoah National Park“Delightful … a fresh and engaging way to tell the climate change story.”—Laura Helmuth, senior science editor, Smithsonian“Wilderness adventurers like Lanza are the advance scouts of global warming, bringing back firsthand testimony from pristine landscapes that powerfully corroborates what climate scientists are telling us about our changing planet. But this eyewitness report is much more than an impassioned polemic: it’s also an entertaining collection of backcountry anecdotes—surprise encounters with grizzlies, anxious moments on glaciers and wild coastlines, jaw-dropping views from remote summits—that bring climate change to life in a way that’s more palpable and persuasive than any data chart. Above all, Before They’re Gone is a fetching love letter to Mike’s wife, children, and friends and to the wild places he treasures as only a hiker, climber, and explorer can.”—Jonathan Dorn, editor in chief, Backpacker |

|

| Table Of Content | Prologue: Inspiration Chapter 1) Deepest Earth Chapter 2) How Does the Water Go Up the Mountain? Chapter 3) The Distant Rumble of White Thunder Chapter 4) In the Long Shadow of “The Mountain” Chapter 5) Along a Wild Coast Chapter 6) The Backbone of the World Chapter 7) If a Tree Falls Chapter 8) Searching for Dr. Seuss Chapter 9) The End of Winter Chapter 10) Going Under Epilogue Acknowledgments Sources |

| Excerpt From Book | Chapter 6: The Backbone of the WorldAugust 2010We hear the menacing snarls and let our eyes trace the sound to itssource. Just a few hundred feet below where we stand at 7,050-foot LincolnPass in Montana’s Glacier National Park, two grizzly bear cubs tussleplayfully where this open, rocky mountainside meets a sparse coniferforest. Vigilantly close by, their mom vacuums her nose over the ground,searching for tidbits. A plus-size lady, she has a weight lifter’s physiqueatop hips and legs that might cause a self-conscious bear to frown at herreflection in a lake. But she moves like a four-hundred-pound balletdancer, hinting at speed and power that we cannot fathom.Seeing her arouses a feeling so primal that few words even form inour minds or emerge from our mouths. Our skin prickles, our throatsturn to sandpaper. If we possessed ears that normally drooped down,at this moment they would stand straight up. If we had the option, wewould dive without further contemplation into a claustrophobic burrowand cower for a long time.But we have no burrow. And the bears are just four or five steps offthe trail we have to descend.As any backpacker or armchair adventurer understands, this representsthe worst possible circumstance. A grizzly bear alone might normallyflee from the sounds and odors of humans, probably before thepeople even realized a bear lurked nearby. But other than a polar bear, a griz sow with cubs is arguably the most fearsome, ferocious terrestrialbeast in the Americas. She may perceive any sizable creature in her vicinityas a threat to her babies. Every two or three years in the western U.S.or Canada, a sow horribly mauls or kills some hapless person guilty ofno more than stumbling upon the same patch of earth at exactly thesame moment as her cubs. In July 2011, a sow with cubs killed a 57-yearoldman hiking with his wife in Yellowstone.So we wait, hoping the bears will move on. There is no wind; theymay not smell us. They disappear into the woods, but we periodicallyhear their growls, too close to the trail for us to consider venturing downthere. An hour drips by like candle wax.Three other hikers, two men and a woman, come along, headingin our direction. After a brief, lively huddle, we agree on a plan: we willwalk in close formation down the trail, making abundant noise. Bears,according to conventional thinking, will not engage this large a groupof people.But apparently, these grizzlies did not read the rulebook.As we buckle on backpacks, the woman says, gravely, “There are thebears.” When we look downhill, she clarifies, “No, behind you.”We spin around. The sow, not thirty feet away, saunters noiselesslyacross the grassy meadow we’re standing in, her cubs in tow. While wewere strategizing how to outwit them with our superior intellects, theyhad pulled off a perfect flanking maneuver. From this close, we see hershoulder muscles rippling, the fur backlit by sunlight, and razor teethdesigned for tearing through flesh as her mouth gapes open.Then she sniffs the air and swings her head to stare directly at us.If there is a national park that seems created to fulfill the grandestdreams of backpackers, it is Glacier.Straddling the Continental Divide hard against the Canadianborder, the northernmost U.S. Rockies resemble a collection ofmountain-scale kitchen implements—meat-cleaver wedges of billionyear-old rock and stone knives lined up in rows that stretch for miles,everything standing with blades pointed upward. More than a hundredof them rise above eight thousand feet, the highest exceeding tenthousand feet.Streams collect the runoff from fields of melting snow and ice,pouring down mountainsides, shouting loudest when crashing over innumerablecascades and waterfalls. Late-afternoon sunlight glints offpebbly creeks spilling from lakes, the water’s surface sparkling like diamondsslowly twisting. Geological strata stripe mountainsides in parallelbands. Wildflowers in a palette of colors dapple vast, treeless tundraplateaus.The Blackfoot called these mountains “the backbone of the world.”The description fits a place where the land vaults up so dramaticallyfrom the very edge of the Plains—and where Triple Divide Peak is oneof only two North American mountains that funnel waters to threeoceans: the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic.Swiss-born paleontologist Louis Agassiz, hailed as one of the greatestscientists of his time, comprehended the origins of places like thefuture Glacier National Park. In the 1840s, he theorized that an ice agehad once locked up much of the planet. His ideas explained the signs ofglaciers in Europe and North America where they did not exist: groundscraped down to striated bedrock, and massive “glacial-erratic” bouldersdeposited in meadows and forests by some mysterious but powerfulforce. Today, a glacier in the north of this park is named for him.The renowned writer George Bird Grinnell, who began lobbying todesignate the area a national park after visiting in the 1880s, called thesemountains “the Crown of the Continent.” The Great Northern Railway,hoping to bring in paying tourists, dubbed the area “Little Switzerland.”But in one important aspect, it differed from the Swiss Alps as muchas Central Park from the Serengeti: unlike the settled Alpine valleys andmountainside meadows, the Northern Rockies were an intact, pristinewilderness. Today, some 90 percent of the park’s million acres remaininaccessible except to those willing to explore on foot.Glacier is among just a few U.S. wild lands outside of Alaska thathost a nearly complete array of the continent’s native megafauna. Onlytwo are missing: the bison and woodland caribou. Sixty-two mammalspecies live here, and 260 kinds of birds are seen. Glacier and neighboringWaterton Lakes National Park in Canada have been designatedan international peace park, an international biosphere reserve, and aWorld Heritage Site.A backpacker on any of the park’s more than seven hundred milesof trails may lose count of how many times she sees cliff-scaling, beardedmountain goats. Many backpackers go home with breathless tales ofwalking past that most regal of creatures, the bighorn sheep. Some—likemy friend Geoff Sears when we took a trip here together—tell of leavinga sweaty T-shirt hanging outside to dry overnight, only to discover iteven more soaked in the morning because deer have gummed it for thesalt from perspiration. Hikers in early fall might hear bull elk bugle orsee two bull moose clashing massive antlers.Encounters with black or grizzly bears—both number in the hundredshere—occur rarely, for one simple reason: a bear will usually detectthe humans first and avoid them. This dynamic undoubtedly servesthe interests of both parties. A bear attacking people ultimately loses, aspark officials will destroy it. And no one with a healthy attitude towardlife wants to cross paths with a grizzly.When Lewis and Clark explored the American West, the grizzlynumbered an estimated 50,000 and ranged over two-thirds of the contiguousUnited States, from the Canadian border to Mexico to Ohio.While more numerous in Canada and Alaska, about 1,400 remain inthe Lower 48, and they live only where humans tolerate them. Morethan seven hundred bears dwell in Glacier and the surrounding nationalforests, and another six hundred in Greater Yellowstone. Small, at-riskpopulations hang on in remote mountains in Washington, northernIdaho, and northwestern Montana.No other species in North America shapes our perception of wildernessas definitively as the grizzly. There are wild lands with grizzlies, andthere are those without, and they are as far apart in our minds as terroris from thrill.Where they live, we enter the woods with a heightened alertness.Every dense copse of spruce trees or tall bushes potentially harbors amenace. Come upon a steaming pile of scat the size of a soccer ball, andyou will wonder which direction the bear went and which you shouldgo. We are not so far evolved from our hunter-gatherer ancestors to havelost our innate aversion to being eaten.Encounter a great bear close up and, regardless of how you had planned to react, you may find yourself overwhelmed by one instinctivethought: flee. You backpedal, maybe stumble. You might reach for thepepper spray on your belt or forget it’s there. You know in your bonesthat you possess little control over what happens next.Terror hits hard right in the gut and takes the wind out of you. Iknow, because I’ve felt it.When that sow grizzly and her cubs crept up so stealthily behindmy friend Jerry Hapgood and me at Lincoln Pass on that late-summermorning, she not only Tasered us with one of the biggest, voice-seizingfrights of our lives; she also clarified an unsettling truth: when you walkthrough country inhabited by grizzly bears, you see and hear themeverywhere—except the ones that are actually right on top of you. Toour good fortune and vast relief, that sow and her cubs merely continuedon their way, giving us no more than a glance.Now, eleven months later, I’m backpacking that same trail in Glacierwith my wife and children, on another perfect summer day inmountains carved from glaciers but designed in dreams.And I am thinking about bears. |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.