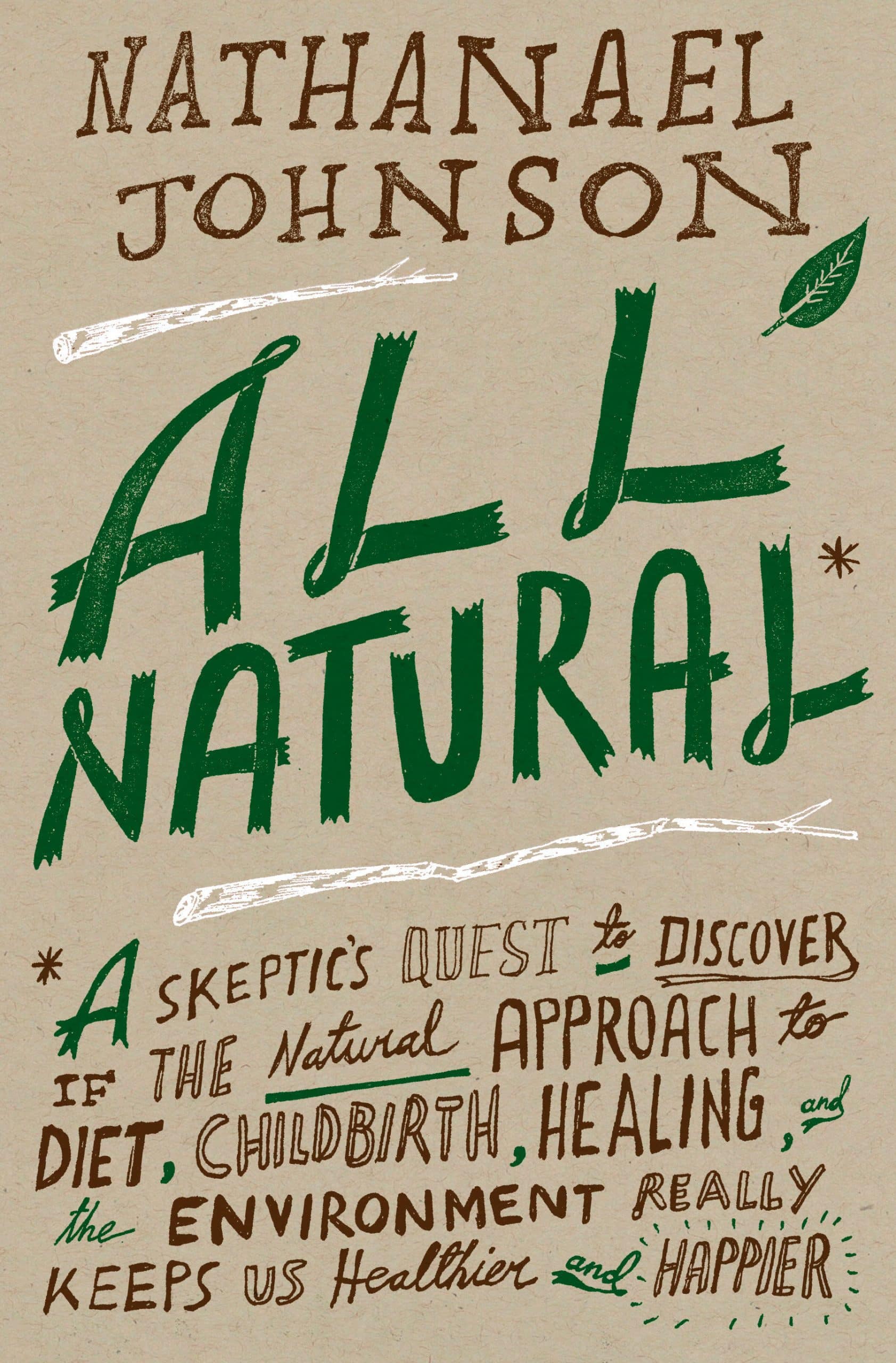

All Natural*: *A Skeptic’s Quest to Discover If the Natural Approach to Diet, Childbirth, Healing, and the Environment Really Keeps Us Healthier and Happier

21.00 JOD

Please allow 2 – 5 weeks for delivery of this item

Description

In this age of climate change, killer germs, and obesity, it’s easy to feel as if we’ve fallen out of synch with the global ecosystem. This ecological anxiety has polarized a new generation of Americans: many are drawn to natural solutions and organic lifestyles, while others rally around high-tech development and industrial efficiencies. Johnson argues that both views, when taken to extremes, can be harmful, even deadly.Johnson, raised in the crunchy-granola epicenter of Nevada City, California, lovingly and rigorously scrutinizes his family’s all-natural mindset, a quest that brings him into the worlds of an outlaw midwife, radical doctors, renegade farmers and one hermit forester. Along the way, he uncovers paradoxes at the heart of our ecological condition: Why, even as medicine improves, are we becoming less healthy? Why are more American women dying in childbirth? Why do we grow fatter the more we diet? Why have so many attempts to save the environment backfired?In All Natural* – a sparklingly intelligent, wry, and scrupulously reported narrative – Johnson teases fact from faith and offers a rousing and original vision for a middle ground between natural and technological solutions that will assuage frustrated environmentalists, perplexed parents, and confused consumers alike.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.62 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 2.82 × 15.85 × 23.55 cm |

| PubliCanadanadation City/Country | USA |

| by | |

| Format | Hardback |

| Language | |

| Pages | 352 |

| Publisher | |

| Year Published | 2013-1-29 |

| Imprint | |

| ISBN 10 | 1605290742 |

| About The Author | Nathanael Johnson is an award-winning journalist who has written features for Harper's, New York, Outside, and San Francisco magazines and produced stories for National Public Radio and This American Life. He studied with Michael Pollan at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. He lives in San Francisco. |

“Engaging look at the merits of nature versus technology…Johnson's investigation is both horrifying and amusing, and readers will relish the colorful, witty writing and find much food for thought.” —Booklist“[Johnson] presents a refreshing optimism that neither extolls the organic to the point of supporting pseudoscience nor negates the value of scientific advancements…The book strikes at the heart of hot-button issues with an Everyman appeal.” —Kirkus“It's hard not to smile when [Johnson] writes tenderly about growing up as a naked back-to-nature kid raised on zucchini in a world of space-pod juice packets like Capri Sun and spreadable cheese food.” —Spirituality & Health Magazine“I had so much fun reading All Natural that I found myself reading passages aloud to my husband and summarizing Johnson's findings to my kids' teenage friends.” —RANDI HUTTER EPSTEIN.COM + Psychologytoday.com“His book is not only a fascinating read for those who want to get to the bottom of issues such as raw milk and home birth, but it is also a call for more sensible decision-making…Johnson's personal journey through the book, which he recounts with sparkling humor, begins with him shopping for the best ideology and ends with him trying to operate without any ideology–seeing 'the world both ways at once, with both eyes open.'” —CONSERVATION MAGAZINE“What's really welcome about his deeply reported book, All Natural, is that [Johnson's] upbringing makes the investigation of nature vs technology fun as well as thought-provoking…All Natural brings the arguments to life through a cast of wonderful farmers, neighbors, doctors, midwives and Johnson's own parents.” —LOS ANGELES TIMES“This is a quirky and fascinating book, one of a kind. Johnson's parents were stalwart hippies and raised him according to the orthodoxy that whatever is most natural is best, so: natural childbirth at home, no sugar in the diet, no clothing on the baby (not even diapers!), natural medicines etc. Johnson decides to examine the scientific basis of these practices, and lo and behold, discovers more justification than you would expect for a radically less-industrialized approach to managing the various stages of development, life and death.” —Michael Pollan, Barnesandnoble.com |

|

| Excerpt From Book | CHAPTER ONEA HEALTHY STARTBIRTHHanging on the wall beside my desk is a photograph from my first morning on earth, and as I've endeavored to organize my thoughts on natural childbirth–and on the wisdom of trusting nature in general–my eyes have strayed to this image so often that it has taken on iconic significance. The family is captured in black and white, lounging on homemade corduroy pillows, which lean against the dark grain of a redwood wall. A mobile hangs half out of frame–balls of yarn dangle from a coat hanger. The two preteens in the picture are unfamiliar to me: They are my half brother and half sister, but I remember them only as adults because their father, from my mother's first marriage, took them into his custody a few years after this picture was made. I'm the baby in the center, contorted into a posture of spastic newborn disorientation. My brother smiles down at me; my sister looks into the camera from under a Cal Bears visor; Dad, thickly bearded, long-haired and leonine, lies with an arm around me; Mom lounges in back, radiant and beautiful, which is a bit staggering since she'd recently delivered me to that bedroom. What sets it apart from most newborn photos, however, is not what's in the picture, but what's missing: There are no IV towers, no ID bracelets, no hospital-issue blankets, or bassinets of industrial plastic to interrupt the natural-fiber aesthetic. In this family–the picture says–we don't fear nature, instead we embrace it, moving in harmony with its cycles. It was taken on October 9, 1978.I only got around to asking my parents about the photo a few months before my wedding. That's probably because I'd never thought much about birth or babies until Beth, my fiancee, made having children a precondition to her acceptance of my marriage proposal. Fatherhood, which had been a theoretical possibility, assumed an onrushing inevitability and, suddenly, it seemed important that I develop a position on progeny politics, starting with birth. Beth had no bias against hospital births. We came from opposite sides of the cultural divide: While my father had made his living as a psychotherapist–exercising extrapolations from Jung on dreams and ephemera- -her father had worked as an orthopedic surgeon, exercising concrete mechanics on bone and muscle. A few months after I was born at home, she was born via scheduled Caesarean section. If I was going to insist on homebirth and breastfeeding and all the other natural practices my parents had embraced, it seemed only fair that I discuss this with Beth while she still had the option of finding a less doctrinaire partner in parenting. And, if I was going to articulate my position on these issues, it no longer seemed acceptable to base it on the hazy warmth I got from a picture. I started my remedial education by calling my parents and asking them to share their recollections.My mother, Gail, had given birth to my brother and sister in a Berkeley hospital. Brent was her first, born in 1966, and it had taken nine hours and forceps to convince him to exit. She'd been left alone during most of her labor and perhaps it was the resulting memory of neglect, or perhaps the way the forceps had cut and welted Brent's head, or perhaps the general feeling of helplessness associated with being a patient in any hospital– whatever the reason, the experience felt unnecessarily traumatic. My sister, Erin, was born at the same hospital in 1970, and though that birth was uncomplicated, it had left Mom with that same vague sense of wrongness.By the time I came along, things had changed. The agent of that change was a six-foot-two poet with blue eyes, a swimmer's body, a declamatory basso voice that rumbled up from his belly, and wavy brown hair that cascaded down between his shoulder-blades. He had a name like some fictional frontiersman: Belden Johnson. Dad swept into Mom's life like a flood, overflowing her banks and casually demolishing the contours that had contained her. She exchanged her tightly restrained role as immaculate hostess and lawyer's wife for the liberty and chaos of the counterculture. The photographs from this time show a luminous woman, smiling, with straight hair to her waist over simple tunic dresses.After my parents began living together, they would periodically rent a cabin in the California wine country where they'd hole up for days on end with a grocery bag of food and occasionally a few tabs of LSD. My conception was very likely buoyed on that psychedelic tide. They both remember feeling, that night, in that cabin in Sonoma County, the utter certainty that they had just made a baby. Though it's unlikely that the chemicals would have altered the dance of the gametes in any biological sense, this event does seem metaphorically significant: My parents, who would become so committed to safeguarding their children from the corrupting influence of modern technology, had unwittingly undermined themselves, baptizing my first moments of mitosis in Timothy Leary's bioluminescent broth. They thought they were raising an earth child, but my ecosystem was already polluted with synthetics.My parents, like all parents I suppose, later tried to put from their minds the possibility that they might have ruined their child. When I pressed Dad on this point he managed to recall only vague trepidation."But, Dad," I said, "if you were, you know, um, tripping, weren't you worried that you were going to get a really messed-up baby?""That certainly did cross my mind," he said, hesitantly, before settling on a flip response: "and obviously it was true."Somehow, the knowledge of this contamination was less disturbing than the shadowy dangers of environmental pollution and industrial toxicology of California in the 1980s, over which my parents had little control. Teasing aside, from the moment of conception Dad did everything he could to shelter my newly formed embryo from all insults–chemical, psychological, or physical. I would be his first child, and he threw himself headlong into parenthood.Realistically, however, there wasn't much he could do before birth and absent any practical outlet for his creative paternal instinct, he became ferociously and dubiously helpful. He read poetry and sections of the Iliad to Mom's abdomen. He built a deck off the bedroom so that when I emerged, I could lie in the sun. He played music for me and made up snatches of a lullaby in French (Mon petit bebe, tu es tres joli), which he'd sing over and over. The pinnacle of Dad's efforts, however, was the "beasty-yeasty": a concoction of brewer's yeast, yogurt, and granola, blended until smooth. The idea was to prevent morning sickness–brewer's yeast contains vitamin B, which seems to ease some women's symptoms–but the beasty-yeasty was where Mom drew the line."You couldn't exactly drink it," she said. "You kind of had to gag it down." No matter how unpleasant the retching, Mom would explain to Dad, the expulsion of vomit was preferable to drinking it in this ersatz form.Behind all this action were hours of study. Many people were becoming alarmed enough by the state of childbirth around that time to write books about it, and Dad read everything he could get his hands on. Birth Without Violence, by Frederick Leboyer, had just come out, suggesting that, rather than enduring the bright lights and cold metal of a delivery room, babies should be placed into warm water to mimic the environment of the womb. And Suzanne Arms's Immaculate Deception made the convincing case that many of the technical birthing interventions were not employed out of necessity, but because a historically male medical culture presumed that women's bodies were inherently dysfunctional.None of this was foreign to my father, who'd been born without medical assistance. His parents–a Washington bureaucrat (father) and professor of English (mother)–were in many respects conventional citizens of the buttoned-down 1950s, but they had occasionally indulged their own attraction to nature's way: in birthing babies, in growing their own food, and in milking their own goats. There was another even more powerful factor working to convince Dad of the superiority of home-birth. He explained matter-of-factly to Beth and me over breakfast one morning that while in therapy he'd relived his own birth–he'd actually felt sensations and emotions that he interpreted as neonatal memory. "I know," he said, looking at me with a little rumble of bass merriment. "I can tell, that's got your skeptical mind going."Some of the details he'd recalled from his birth were specific enough for him to check. Most convincingly, he remembered experiencing the panicked feeling that his shoulders had become stuck in the birth canal, a detail that his mother supposedly later confirmed. "She was shocked," he said. "She asked me how I could possibly know that had happened." Dad lifted his hands heavenward at this revelation, as if to say, "How else can you explain it?" For him, the experience of reliving his birth had been so profound that he became a therapist, leading others on the same journey into memory. The tenets of this practice, called primal therapy, hold that the psychic scars of birth and babyhood often form the foundation of self- destructive habits in adults, and that healing this residual infant pain is the way to dissolve the emotional stumbling blocks people end up tripping over throughout their lives. The experience of leaving the womb, Dad was convinced, was formative. Babies born via Caesarean section, he said, often become adults who drift along without taking initiative, letting others determine their direction in life.I'd always avoided thinking too deeply about Dad's belief in the power of neonatal psychology because the whole business made me a little queasy. It just didn't square with my experience of the way the world worked. My friends who were born via Caesarean were not detectably different than those who had passed through the birth canal. And the idea that a person's emotional architecture is defined by his experiences on day one was, for me, uncomfortably similar to the notion that personalities are determined by the stars under which they are born. Most of all, it bothered me that I had only my father's non-verifiable experience as evidence.In the decade before I was born, however, my father's theory must not have seemed as far-fetched as it does today. Back then–when young men were being drafted to firebomb villages in Vietnam; and all the writers seemed to be drinking themselves to death in the suffocating normalcy of the suburbs, or dropping out and joining communes; and every inspirational leader was being assassinated; and the police were firing tear gas at the rioters a few blocks away in Berkeley–the idea that the psychic trauma of medicalized birth had created a generation of damaged people seemed plausible to a lot of well-respected psychologists and sociologists. Mom was also immersed in the literature of counter-cultural birth. She read the stories of doctors performing Caesareans in order to make their tee time. She saw a film, shot to prepare Navy wives for birth, full of searing images: women strapped into stirrups, drugged, and casually cut open fore and aft to hasten birth. She was convinced that she (and I) would be safer at home. "It seemed like a hospital birth was insane and inhumane," she said. "There was no question in our minds."My parents would not be dissuaded. They had found a doctor who was just as radical as they were: Lewis Mehl, who had published one of the first peer- reviewed studies on modern-day homebirth in the United States. When my due date came and went, Mehl explained that the risk of stillbirth increased for babies who stewed for too long, but my parents, confident in their choice, simply smiled and said that I would emerge when I was ready.I was ready three weeks later. It was early October, when the heat spills over the coastal mountains into the San Francisco Bay. In autumn it's as if someone has opened the oven door to California's Central Valley, and plumes of summer-forged air flood down the delta to cut back the fog. Flowers burst into bloom again in this weather, and Mom must have noticed them as she walked down Benvenue Avenue. It was a quiet neighborhood, where trees shaded tall houses. She had recognized the pattern of contractions, and had asked a friend to come over and look after Erin and Brent. When she returned, she found that they had baked a heart-shaped birthday cake. Mom called the midwife, then went upstairs. There were a few hours of intense labor, and some pain: Years earlier she'd hurt her back horsing around with the kids, and the contractions triggered spinal spasms. The night fell and brought slips of cool ocean air through the windows. Someone lit candles. When progress seemed to slow, Dad went looking for upbeat music. He put a Chieftains record on the turntable, and I emerged to an Irish hornpipe. My brother cut the umbilical cord. My sister wiped the sweat from Mom's forehead. As a neo-Nate, I was massive: They weighed me on a fish scale, and it was clear that I exceeded 11 £ds, though it was hard to judge by exactly how much because the load was close to the instrument's limit. (Nine £ds is a lot of baby, 11 £ds is an orca.) Mom held me and I began to nurse.What came next spoiled, or at least complicated, the moral of the story. The scene had become quietly celebratory as the newly enlarged family crowded into the room. The sun rose. A family friend took the photograph that now hangs on my wall. But the midwife was nervous. It's normal for some blood to come with the afterbirth, but the flow was not tapering off. Dr. Mehl, who arrived shortly after the birth, said that it looked a lot like a postpartum hemorrhage. My parents didn't know it, but postpartum hemorrhage was the leading cause of maternal death (and it still is, due to the lack of skilled birth attendants in the developing world).Mehl saw that he quickly had to decide whether to take Mom to the hospital or act on his own. He took a coin from his pocket and flicked it into the air. Heads. He cleaned one arm, then reached up into my mother's uterus to scrape away the bit of placenta that had not delivered and was preventing the blood vessels from closing. The pain was severe, worse than any part of the birth. Mom closed her eyes and relaxed, willing herself out of her body to a place where she could observe the sensations from a detached remove. She was so successful, so serenely still, that everyone watching panicked."Oh my God, she passed out," someone shouted. "Stay with us, Gail," the midwife urged.Mom was thinking, Shut up, I'm fine! When she told me the story, she laughed ruefully and said, "It's just pain." |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.