No gift registry found click here to create new registry

Cart contain Gift Registry Items cannot add products

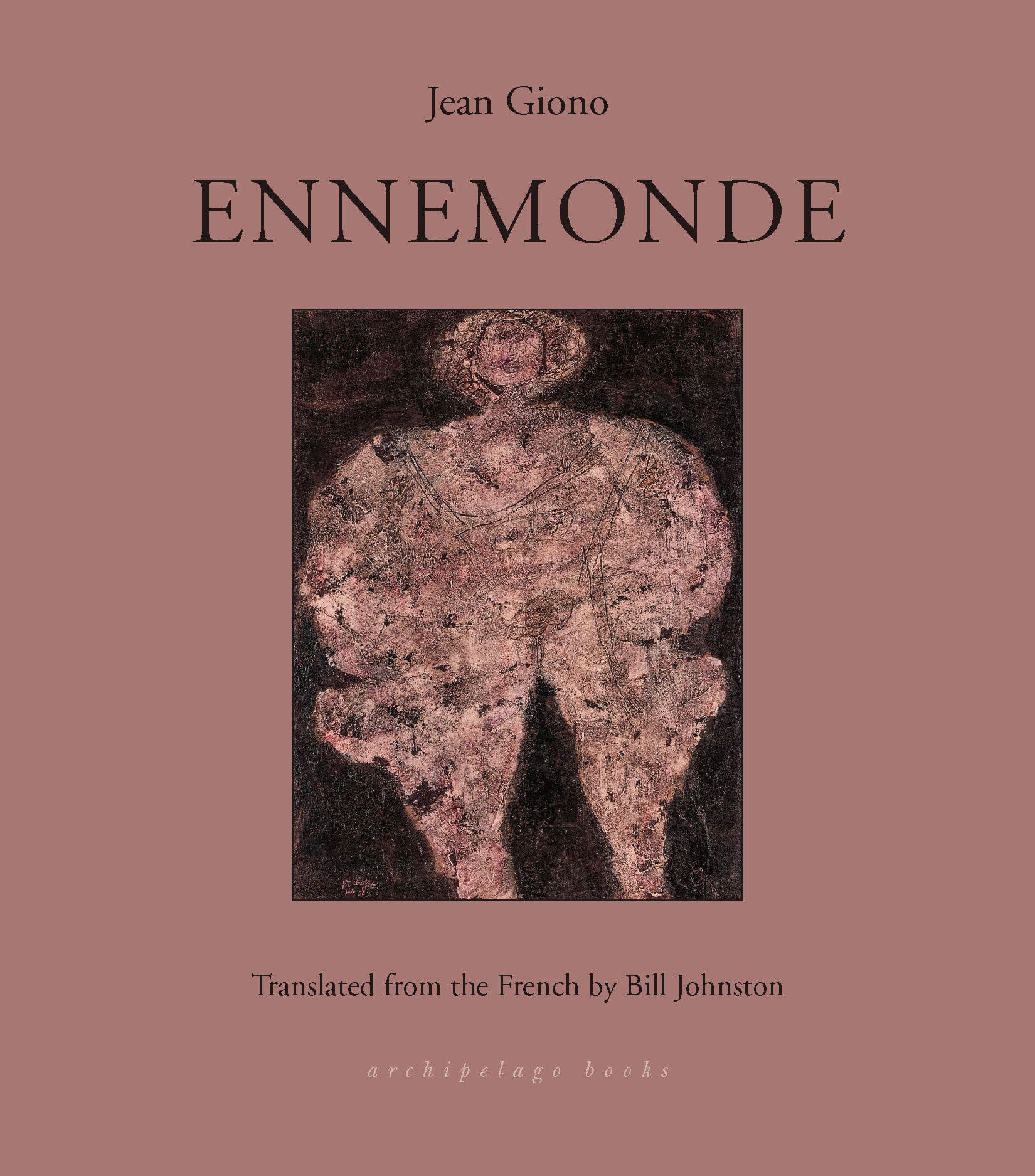

Ennemonde:

14.50 JOD

Please allow 2 – 5 weeks for delivery of this item

Add to Gift RegistryDescription

One of the final novellas by the acclaimed French writer Jean Giono, Ennemonde is a fierce and jubilant portrait of a life intensely livedEnnemonde Girard: Obese. Toothless. Razor-sharp. Loving mother and murderous wife: a character like none other in literature. In telling us Ennemonde’s astounding story of undetected crimes, Jean Giono immerses us in the perverse and often lurid lifeways of the people of the High Country, where vengeance is an art form, hearts are superfluous, and only boldness and cunning such as Ennemonde’s can win the day. A gleeful, broad sardonic grin of a novel. “Roads move cautiously around the High Country…” So begins the story of Ennemonde, but also of her sons, daughters, neighbors, lovers, and enemies, and especially of the mountains that stand guard behind their home in the Camargue. This is a place of stark and terrifying beauty, where violence strikes suddenly, whether from the hand of a neighbor or from the sky itself. Giono captures every wrinkle, glare, and glance with wry delight, celebrating the uniquely tough people whose eyes sparkle with the cruel majesty of the landscape. Full of delectable detours and startling insights, Ennemonde will take you by the hand for an unforgettable tour of this master novelist’s singular world.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.17 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 1.24 × 13.26 × 2.72 cm |

| Author(s) | |

| Format Old` | |

| Language | |

| Pages | 150 |

| Publisher | |

| Year Published | 2021-9-14 |

| Imprint | |

| Publication City/Country | USA |

| ISBN 10 | 1953861121 |

| About The Author | JEAN GIONO was born and lived most of his life in the town of Manosque, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Largely self-educated, he started working as a bank clerk at the age of sixteen and reported for military service when World War I broke out. After the success of Hill, which won the Prix Brentano, he left the bank and began to publish prolifically. Imprisoned at the beginning of the Second World War for his pacifist views, he was once again wrongly imprisoned for collaboration with the Vichy government and held without charges at the war's end. Despite being blacklisted after his release, Giono continued writing and achieved renewed success. He was elected to the Académie Goncourt in 1954.Bill Johnston is the Chair of the Comparative Literature Department at Indiana University. His translations include Wieslaw Mysliwski's Stone Upon Stone, and Magdalens Tulli's Dreams and Stones, Moving Parts, Flaw and In Red. His 2008 translation of Tadeusz Różewicz's new poems won the inaugural Found in Translation Prize and was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Poetry Award. |

"[Bill Johnston's] translation is never static; it captures or even reveals the suspense and the passion present in the original work . . . Defying the stereotype of a strictly Provençal, folkloric, local writer, Giono reveals his entire cultural universe with great abandon and relish." — Alice-Catherine Carls, World Literature Today"Ennemonde is a novel of nature, a novel that might tells us something about the gap between humanity and its environs . . . The sky is black, the trees – beeches, chestnuts, sessile oaks – are infinite, the rocks reverberate, and the peasants are murderous . . . We are in the realm of a naturalized Nietzsche here: what is valuable is what sustains and enhances life . . . Giono troubles us, asks us to pay attention, and finally . . . Giono shows us what one can see if one looks."–Duncan Stuart, Exit Only"Giono's writing possesses a vigor, a surprising texture, a contagious joy, a sureness of touch and design, an arresting originality, and that sort of unfeigned strangeness that always goes along with sincerity when it escapes from the ruts of convention." –André Gide, unpublished letter"For Giono, literature and reality overlap the way that waves sweep over the shore, one ceaselessly refreshing the other and, in certain wondrous moments, giving it a glassy clearness." –Ryu Spaeth, The New Republic "Giono's voice is the voice of the realist; his accents are the accents of simplicity, power and a passionate feeling for a land and a people that he must love as well as understand." –The New York Times "Giono's prose is a singularly fine blend of realism and poetic sensibility. Essentially a poet, he has an acute faculty of penetration, a lucidity of spiritual vision, and a tender sympathy." –The Washington Post"Giono offers a steady flow of rich imagery and biographical tidbits about the denizens of a mountainous region of southwestern France in this sensual pastoral . . . The characters often feel like a manifestation of the rugged land they inhabit: the farm girl Ennemonde, for instance, born near the turn of the 20th century, possesses “a fruitlike beauty.”. . . Giono achieves an engaging and worldly narration, which grounds the reader in this juicy web of anecdotes." –Publishers Weekly "This sharp little book marks a return to [Giono's] naturalistic themes, but with a bitter bite . . . Ennemonde hurtles onward, clause piled on descriptive clause, as if in every great arabesque of a sentence Giono were trying to encompass the whole of Provence. But he isn’t aiming for grace; no, it’s all spiteful glee in these lines . . . a riotous book." –- Robert Rubsam, The Baffler"Giono creates an atmosphere that is both contemporaneous and timeless…the epic instinct is active." –Ray C. B. Brown "I'm reading Bill Johnston's translation of Jean Giono's Ennemonde, and have come to love the way Giono nestles a kernel of a story inside descriptions of the natural world and its inhabitants, human and otherwise. These plots are organic; they grow out of the soil." –Stephen Sparks of Point Reyes Books via Twitter"The land, rough and wet and unparsable, is what dominates [Giono's] novels, dictating the movement of the plot and the development of the characters. Sitting somewhere between the psychologism of Proust or Gide and the realism of Zola, Giono’s dramas unfold as if the inanimate world were itself the primordial life-breath of the animate one . . . a superb English translation by Bill Johnston . . . Ennemonde is a novel about peasantry and the old Gionian world, but it is also one about art and writing themselves—about the acts of observing, of developing a scale."– Ben Libman, The Review of Uncontemporary Fiction"Even when it feels like the narrator is insulting, criticizing, belittling his rural characters, he is actually breaking them loose from the virtuous and the picturesque. Characters pull the sleight of hand of disappearing into their own environment, knowing nature for something other than scenery, impulse for something other than joyrides . . . The bitter tone of the book, mixed with the transcendently lovely descriptions that are so typical of Giono, has me wanting more than ever to situate the author in his past, present, future . . . [Ennemonde] feels like the culmination of several lifelong struggles."–Abby Walthausen, Asymptote"A tour de force in [its] own fashion . . . Giono (or Gallimard) calls [Ennemonde] a novel but it feels more like a collection of legends, a discursive anthology of the stories told in and about the real and imaginary place called the High Country, and another, distinctly low place called the Camargue." — Michael Wood, The London Review of Books |

|

| Excerpt From Book | Journeys are not undertakenlightly in the High Country. Farms may be five or ten milesfrom their nearest neighbor. Often it would be one solitary mantraveling those miles to see another solitary man; he never doesthis even once in his life. Or else it’d be a whole tribe of adults,children, and old people setting off toward another whole tribeof adults, children, old people – to see what? Women demolishedby repeated pregnancies, red-facedmen, and crooked old folks(and children too) – only to be looked down on by them? Thehell with that. If anyone wants to show themselves, they’ll do it atthe markets. Twenty, twenty-fivemiles separate the villages thatneatly line the circuit formed by the road.In the surrounding country there are beech trees, chestnuts,sessile oaks – beeches that grow more massive the farther outyou go, sessiles that are ever more ancient; far removed from anydealings with men, there are families of birches that are lovelyin summer and that disappear, white against white, in the snow.On the moors there’s lavender, broom, esparto, sedge, dandelion,and then rocks, rounded rocks, as if long ago, up in theseheights, great rivers used to pass through; then finally, in thegreat open spaces are flat rocks, resonant as bells, that repeat theslightest sound – the hop of a cricket, the patter of a mouse, theslithering of an adder, or the wind glancing off these terrestrialspringboards.The sky is often black, or at least dark blue, though giving theimpression black would give – except during the blooming ofthe wild mignonette, whose exquisite scent is so joyful it dispelsall melancholy. The time of the mignonette aside, fine weatheris not cheerful in these parts; nor is it sad, it’s something else;those who find it to their liking can no longer do without it. Badweather is thoroughly seductive too, immediately assuming as itdoes a cosmic air. There’s something galactic, extra-galacticeven,in the way it behaves. It cannot rain here the way it does elsewhere– you sense that God personally sees to it; here the windmatter-of-factlytakes the fate of the world in hand. The stormadapts its ways here: it doesn’t flash, doesn’t make any noise; simply,metallic objects begin to gleam – belt buckles, lace hooks onshoes, clasps, eyeglasses, bracelets, rings, chains. . . ; you have tomind how you go. You often find twenty, even thirty magnificentbeeches struck by lightning all in a row, dead from head to foot,burned to a cinder, upright, black, bearing witness to the factthat things happen in that silence.Dusk is more often green than red, and goes on for a verylong time – so long that in the end you can’t help noticing thatnight has fallen and that now the light is coming from the stars.In these parts the stars light your way; they’re bright enough forpeople to recognize each other when their paths cross. It may bethat you see more stars here than elsewhere; in any case, they’recertainly larger, for there’s something about the air – whetherits purity, which is exceptional, renders the constellations morevivid or whether, as some claim, it contains some substancethat acts like a magnifying glass. Naturally, no one’s going toboast about having been way out in the open in the depths ofnight. Whenever they see it coming on, people skedaddle homebefore it arrives. There’s a way of behaving toward this land thatwas perfected by our ancestors and that has produced excellentresults; indeed, it’s the only way: you shape yourself to it. Everyaccident that’s been seen to happen here – and they’re countlessin number, including many that are strange indeed – comes fromsome infringement of these sorts of rules or laws.There’s nothing more straightforward for example than goingfrom Villesèche to the Pas de Redortier in daylight; it’ll take youan hour at most. The landscape isn’t exactly cheerful, but it’sdoable; all it needs is a bit of will, or passion (if it’s for hunting),or foolishness (if it’s for no reason). But on a day when theclouds are low and dense, and night falls, try then! No one willchance it.The tool that people around here have most often in theirhand is a shotgun, whether it’s for hunting or for, let’s say, philosophicalreflection; in either case, there’s no solution withouta shot being fired. The gun hangs from the stem of a wineglassthat’s been embedded in the wall near the chair where the manof the house sits. Whether this chair is at the table or by thefireplace, the shotgun is always within arm’s reach. It’s not thatthe region is unsafe because of a lack of police; on the contrary,even in the heyday of banditry there was never any crime uphere, except for one incident in 1928, and that one was preciselyabout what everyone is afraid of. Everyone is afraid of loneliness.Families are no solution: at most they’re collections of lonesomepeople who in reality are each heading in their own direction.Families don’t come together around someone; they separate asthey move away from someone. Then there’s metaphysics – andnot the Sorbonne kind, rather the sort you have to bear in mindin confronting irredeemable solitude and the outside world.Monsieur Sartre would not be of much use here; a shotgun, onthe other hand, comes in handy in many situations.It might seem surprising that these peasants don’t grasp thehandles of a plow. The reason is that the peasants are shepherds.That’s also what keeps them beyond (and above) technologicalprogress. No one has yet invented a machine for mindingsheep. The father, head of the family, oversees the flock; the sonor sons are in charge of the small farm that in fact functions as aclosed economy. People only till the acreage necessary for enoughwheat, barley, potatoes, and vegetables to meet the needs of thefamily or the individual, and that is why so many of the peasantsremain unmarried, living alone: in this way they have need of solittle that they spend no more than one month a year scrapingthe earth. |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Related products

-

On backorder 2-5 Weeks to Arrive

Add to Gift Registry3.99 JOD -

On backorder 2-5 Weeks to Arrive

Add to Gift Registry9.99 JOD -

On backorder 2-5 Weeks to Arrive

Add to Gift Registry15.99 JOD -

On backorder 2-5 Weeks to Arrive

Add to Gift Registry12.99 JOD

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.