No gift registry found click here to create new registry

Cart contain Gift Registry Items cannot add products

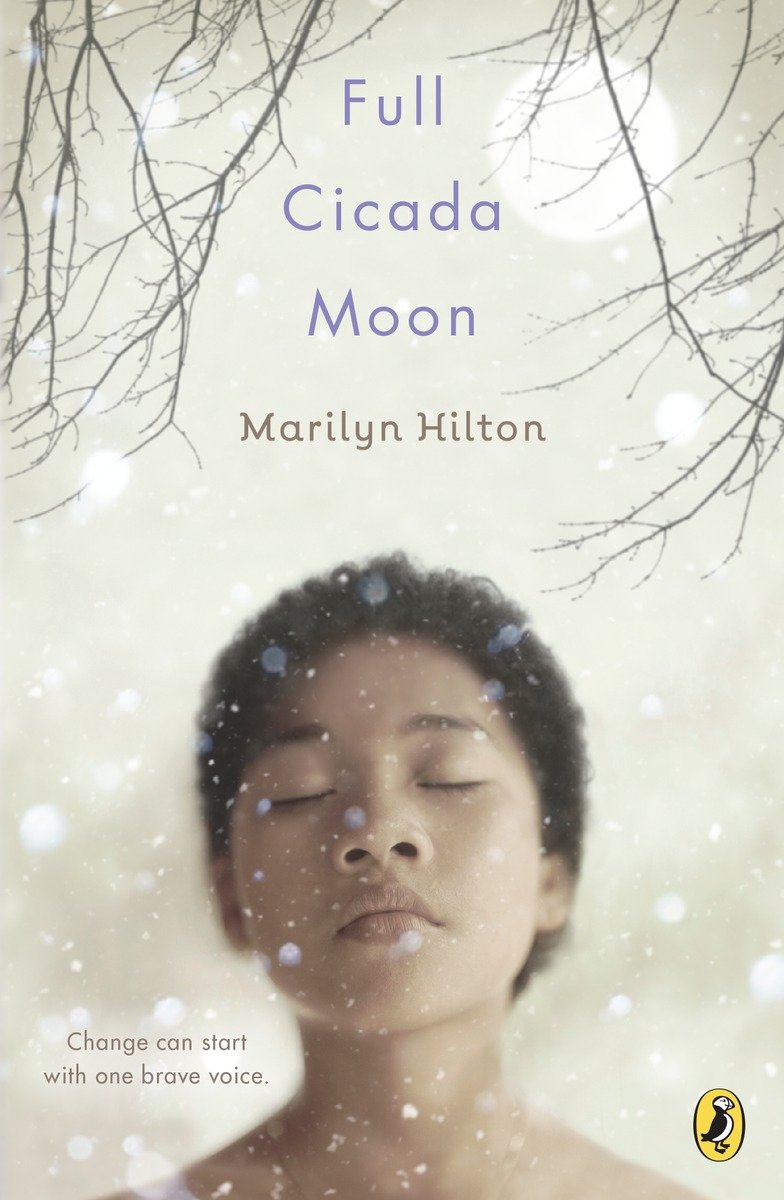

Full Cicada Moon

9.00 JOD

Please allow 2 – 5 weeks for delivery of this item

Add to Gift RegistryDescription

Inside Out and Back Again meets One Crazy Summer and Brown Girl Dreaming in this novel-in-verse about fitting in and standing up for what’s right.It’s 1969, and the Apollo 11 mission is getting ready to go to the moon. But for half-black, half-Japanese Mimi, moving to a predominantly white Vermont town is enough to make her feel alien. Suddenly, Mimi’s appearance is all anyone notices. She struggles to fit in with her classmates, even as she fights for her right to stand out by entering science competitions and joining Shop Class instead of Home Ec. And even though teachers and neighbors balk at her mixed-race family and her refusals to conform, Mimi’s dreams of becoming an astronaut never fade—no matter how many times she’s told no.This historical middle-grade novel is told in poems from Mimi’s perspective over the course of one year in her new town, and shows readers that positive change can start with just one person speaking up.Winner of the 2015-2016 APALA Literature Award in the Children’s category!* “Readers will be moved by the empathetic lyricism of Mimi’s maturing voice.”–Kirkus Reviews, starred review* “This novel stands out with it’s thoughtful portrayal of race and its embrace of girls in science and technical fields. The verse, though spare, is powerful and evocative, perfectly capturing Mimi’s emotional journey.”–School Library Journal, starred review

Additional information

| Weight | 0.28 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 2.67 × 12.7 × 19.54 cm |

| PubliCanadation City/Country | USA |

| Author(s) | |

| Format | |

| language1 | |

| Pages | 400 |

| Publisher | |

| Year Published | 2017-4-4 |

| Imprint | |

| For Ages | 3-7 |

| ISBN 10 | 0147516013 |

| About The Author | Marilyn Hilton (www.marilynhilton.com) has published numerous short stories, poems, essays, and two previous children's books. She lives with her husband and three children in Northern California. |

Winner of the 2015-2016 APALA Literature Award in the Children's categoryA Kirkus Best Book of 2015* "Readers will be moved by the empathetic lyricism of Mimi's maturing voice."—Kirkus Reviews, starred review* "Will resonate with fans of Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming…This novel stands out with its thoughtful portrayal of race and its embrace of girls in science and technical fields."—School Library Journal, starred review* "Perfect for readers who straddle societies, feel they don’t fit in, or need that confirmation of self-celebration."—Booklist, starred review"It is magnificent the way that Hilton sews together words stitching a beautiful quilt of colorfully written poems and sentences. … This is a treasure and truly so different from other books that it is definitely worth your time."—The Denver Post"Brimming with introspection and strong empathetic undertones, Full Cicada Moon is a 'must-read.' "—Kendal Rautzhan, newstimes.com"Through the perspective of this clear-eyed, courageous heroine, Hilton (Found Things) powerfully recreates a time of momentous transition in American history."—Publishers Weekly"Like Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson, Hilton re-creates a time and place in American history and makes it vividly alive through the eyes of an intelligent, spirited girl…Fans of historical fiction and poetry will enjoy this novel."—VOYA |

|

| Excerpt From Book | Flying to Vermont–January 1, 1969I wish we had flown to Vermontinstead of ridingon a bus, train, train, busall the way from Berkeley.Ten hours would have soared, compared to six days.But two plane tickets—one for me and one for Mama—would have cost a lot of money,and Papa already spent so muchwhen he flew home at Thanksgiving.Mama is sewing buttons on my new slacksand helping me fill out the formsfor my new school in Hillsborough, our new town.This might be a new yearbut seventh grade is halfway done,and I’ll be the new girl.I’m stuck at the Ethnicity part.Check only one, it says.The choices are:WhiteBlackPuerto RicanPortugueseHispanicOrientalOtherI amhalf Mama,half Papa,and all me.Isn’t that all anyone needs to know?But the form says All items must be completed,so I ask, “Other?”Mama pushes her brows together,making what Papa calls her Toshiro-Mifune face.“Check all that apply,” she says.“But it says just one.”“Do you listen to your mother or a piece of paper?”I check off Black,cross out Oriental,and write Japanese with a check mark.“What will we do now, Mimi-chan?” Mama asks,which means: Will you reador do algebra, so you’re not behind?“Take a nap,” I say.Mama frowns,but I close my eyesand pretend we’re flying.The bus driver is the pilotand every bump in the roadbecomes an air pocket in the sky.HatsuyumeA jolt wakes me up. I was dreamingmy hatsuyume—the first dream of the new year.If I tell my hatsuyume, it won’t come truebecause in Japanese, speak sounds just like let go.And if my dream meant good luck, I don’t want to let it go.I dreamed I was a bird, strong and brownand fastwith feathers tipped magenta and gold.I shot straight up into the air like a Saturn rocket,then swooped and dove, the sun warming my back.I pumped my wings, then glidedover the desertand the sea.The air filled my lungs,the wind lifted my wingshigher and higherover the mountainsand above the clouds.The moon grew large,and I stretched to touch it.Maybe it was a good-luck dreamand this will be a good yearfor Papa and Mama and me.That’s what I hope.But, what if my hatsuyume meant bad luck?Mama says to let go of your bad dreams by telling them.Papa says to bury your bad dreamsin a hole as deep as your elbow.The ground in New England is frozen,so if I listen to Papa, I’ll have to wait until spring.I’ll listen to Mama insteadand write my dream on paper,so either way—good luck or bad—my hatsuyume will not be spoken.I have never flown beforebut one daysoar.willIWaxing GibbousI studyThe Old Farmer’s Almanacthat Santa had put in my stockingfrom cover to cover.I likereading about the moon,and I’ve memorizedall its names and phases.I knowthe moon tonightis waxing gibbous, almostthe Full Wolf Moon.It has chased us outside the bus windowall the way from Boston,bounding through the sky,skipping across rooftops,dodging treeslike it has one last wordto tell us.I rememberPapa saidif you leave eggs under a waxing moon,all your chicks will hatch.And Mama saidif you make a wish on the moonover your shoulder,it will come true.I whisperto the moon on my shoulder:“I wishall my dreams will hatch.”ReflectionsThis bus lulls.Some people are reading, some are sleeping,two ladies behind us are talking,the baby up front chuckles hoarsely,someone is sipping tomato soup,and in back, Glen Campbell is singing “Wichita Lineman” on the radio.All of us who don’t know one anotherare riding together on this Trailways bus to Vermonton the first night of 1969.It doesn’t feel like oshogatsu, New Year’s Day,because Mama couldn’t make ozoni and sushiand black-eyed peas and collard greens,and we couldn’t sip warm sake from the shallow cups.Mama says she doesn’t care about those thingsbecause we’re traveling to meet Papa.But what bothers heris that no man crossed our threshold this morning(because we don’t have a threshold today),and that means we’ll have bad luck all year.I told her we can find a man to visit our new house,but she said, “Too late.”The lady across the aisle is knitting a scarf.She has been staring at Mama and meever since the sun set.I want to stick out my tongue at her reflection in our windowjust to let her knowI know,but that would disgrace Mamaand disappoint Papa.So, I open the Time magazinewith the three Apollo 8 astronauts on the cover—the Men of the Year—that came just before we left,which Auntie Sachi slipped into my bag at the door,with a note:Have a safe journey.ArrivingI can tell by the way Mama looks at herselfin the window, brushes her bangs to the side,and runs her finger under her eyesthat we’ll be in Hillsborough soon,where Papa, in the tweed coat he calls “professorial,”will meet us.She pops a wintergreen Life Savers in her mouthand passes the roll to me.I take onebecause I want my kiss on Papa’s cheek to be fresh.The bus slows down.A barbershop, an insurance company,a dentist’s office, a grocery storeall slide by. The air pricklesand everyone sits up straight and shifts in their seats,finishes talking to the person next to them.“Hillsborough coming up!” the driver calls.The lady across the aisle winds up her yarnand tucks her knitting into a tote bag. She looks at me againand leans into the aisle. “Are you adopted?”“Nani?” Mama asks me. She must have been daydreamingor she would have asked, “What?”I whisper, “She wants to know where we’re going.”Mama glances at the lady and turns into Mifune.But before she can pretend she doesn’t speak English,I say, “She’s my mom.”The lady looks at me, then at Mama,and shakes her head.“No . . . she’s not your mother.”The bus pulls up in front of a dinerand stops so quickthat we all jerk forward in our seats.The driver cranks a handle andthe door hisses open.He disappears outsideas cold air scampers down the aisle.Papa is waiting in front of the dinerwearing his coatand a red-and-gold scarf, Hillsborough College colors.When he sees me inside the bus, he waves.But I wave harder.Outside, I hold his hand in his pocketwhile he counts our suitcases—four plus my overnight case.The icy air pinches my cheeks,but my heart is warm.He drapes his scarf around my throatand says, “Now you’re the professor.”The knitting lady steps down from the busfor a breath of air.“And this is my dad. See?” I say, and smile.She looks at Papa, at Mama,and back at me. Then,not smiling, she says, “Yes, I see,”and walks toward the diner.When I know Mama and Papa can’t see me,I stick out my tongueso far that it hurts.New HouseOur new house smells like varnish andbalsam needles and mothballs.The floors are all wood, except the kitchen and the bathrooms,which are linoleum,and they creak when I walk around in my socks—which I can’t do for longbecause it’s so cold that my scalp tightens.Halfway up the stairs is a stained-glass windowwith a picture of flowers and butterflies in a garden,like spring.Papa opens the cellar door and flips the light switch.I peer down the dark, dusty staircase.And in the kitchen sink are the bowl and spoon Papa used for his cornflakes this morning.He shows Mama the cinnamon-colored dishwasher built under the counterand the garbage disposal built into the sink.These are firsts for Mama.She opens the dishwasher door and pulls out the top rack.“Hmm,” she says, and that’s all.Papa and I look at each other.We know we’ll find out what that means,but it won’t be now.“This is our room,” Papa says,opening a door down the hall.A big bed with a yellow comforter sits against a wall.Papa is renting most of the furniturebecause we didn’t own much in California.Before Mama and I left Berkeley,she shipped her tall china cupboard and her kotatsu,the low table with a heater underneath.“Where’s my room?” I ask.Papa takes my hand and leads me up a steep staircase.My room is at the top. It’s the biggest bedroom I’ve ever seen.One side of the ceiling slopes halfway to the floorand seats are built under the two windows.“If you don’t like it, you can trade with us,” Papa says.But I say no—so fast that he can’t take this room away.Later, Mama comes upstairs to tuck me in,like I’m five again.But tonight, because we’re in our new house,in our new town, on the other side of the country,I want her to.She sits for a few minutes on my bed,as if she needs to as much as Ineed her to.Papa has had a week to get used to this new house,and Mama and I will catch up.She kisses me good night and tucks the comforterall the way around my chinand goes downstairs. The light glows up the stairs,stretching her shadow on the wall.The sky outside is soft pink, and I smile into my comforter.It is like the soft pink is inside me, resting,breathing with me.Is this house making me feel this way,or the snow outside? Or knowing our long trip is over?Or having a big bedroom upstairsbut hearing Mama and Papa downstairs,and we’re a family again after four months?That’s it—all the good things have come togetherin soft pinkhappiness.First NightThis house creakslike it can’t find a comfortable place to settle into.I toss and turnand can’t find a comfortable spot to sleep in.My clock says 2:18 a.m.I get out of bed and sit at a window.The sky has clearedand the moon sits high in the skylike a pearl button.Stars—bright, cold, voiceless—are winking, but I know that’s because Earth’s heat is rising,the atmosphere is shifting.(A future astronaut needs to know these things.)I wonder if Earth winked at the Apollo 8 astronautswhen they took its picture from the moon on Christmas Eve.Something moves in the next yard.A dog, dark and fuzzy, leaps in the moonlit snow.Then one sharp whistle from the neighbor’s housecalls it inside.Like SaturdayThe sun wakes me up.Ouch! my neck hurtsbecause I’m still sitting at my window.A fringe of icicles hangs outside,and the sun makes little rainbows inside them.I smell coffee and bacon,and I know that hot chocolate is waiting downstairs.No cornflakes for Papa this morning—Mama’s making her special basted fried eggs with onionsand the bacon he loves.Today is Thursday, but it feels like Saturdaybecause this is still school vacation.Thursday is the only day that doesn’t have a personality,so today it borrowed Saturday’s.Mama has already set out her maneki-neko,the cat statue that waves, so we will have good luck from the start.It makes our new house feel more like home.“What’s your plan today, Meems?” Papa asks at the table,the newspaper open in front of him.What I really want to do is see that dog again,but I shrug and say, “Explore.”“It’s cold outside,” Mama says. “Wear your warm clothes.”Papa looks up from his paper. “And do not leave the yard.”Next Door BoyWood smoke hangs in a blue haze outside,and far offa chain saw buzzes through the air.An empty coop in our backyard is covered in snowlike a tiny alpine chalet,but in the spring it will be filled with turkeys.My lips stick to my teethand my nostrils are stuck shut. My chest hurtswhen I breathe this icy air.I’ll warm up by making a snowman.This snow is too deep for rolling three balls for his body,so I pack it into a mound,then sculpt him with my hands.I pack a lemon-size ball for his nose, poke holes for his eyes,and draw a big smile with my thumb.By the time I’m done,my skin prickles with sweat under my clothes,my nose runs,and my legs shudder.A boy steps out of the house next doorand kicks snow down the back steps.The dog from last night bursts past him,toppling the boy to the snow.“Pattress!” he calls, laughing.But she wanders away from him, snufflinglike a steam train.Even across our wide yards, I can seethe boy’s cheeks are red on his pale skin,slapped by the cold.Pattress wags her long, pointy tail.“Hi,” I say, raising my hand, sniffling.The boy raises his hand and nods, thengoes back into the house,calling, “Come on, Pattress.”The brown dog looks at me, then at the steps,and follows the boy inside.Ready for SchoolThese are the new slacks that Mama sewed,butterscotch corduroy with three black buttons at the waist,because four would be bad luck.This is the sweater that Auntie Phoenix sent from Baltimore,tangerine and fluffy,scratching my wrists and neck.These are my tightsand my secondhand boots with a run-down right heelthat crunch in the snow, leaving waffle footprints.This is the wool coat that Mama worethe winter she married Papa in Japan.And mittens with snowflakes on each palmand a long scarf to shield me from the tiny wind daggers.When I breathe, my cheeks and chin feel moistand cold at the same time.These are my frozen eyelashesand my Popsicle nose.You have to wear a lot of clothesjust to go to school in Vermont.First DayPapa doesn’t want me to take the school bus,so he’s driving me on his way to the college.When the wind blows the snow, it makes a rainbow.Rainbows mean hope. I hope for a good day,good teachers, a good friend.Deep in my pocket, I touch the round of omochiand a square of corn breadthat Mama wrapped in wax paperso I can remember our small, late oshogatsu.I wish we didn’t have to live out in the sticks,but Mama wants to raise turkeys and grow vegetables,so even in spring, Papa will take me and bring me home.Maybe there’s another reason we live two miles from townand Papa drives me to school.Even if we lived in town,in the kind of house other professors live in—like that white-shingled Victorian with the black shutters—would Papa escort me every morningand stand guard after the last bell?RulesI thought that Papa was going to drop me offin front of my new junior high.Instead, he turns into the drive and parks in frontof the PRINCIPAL sign.Our car is a green Malibu, which Papa droveall the way from Berkeley to Hillsborough.One day he’ll tell us about that tripall at once.Or, maybe he has been telling it all along,the way snowpack grows:a million tiny flakesdriftingone by one,but I haven’t been listening.“Everything cool?” he asks.I look out the windshield at the white clapboard building,the wide steps up to the front doors,the tall windows framed in green sashes.“It’s cool,” I say, because it’s what he wants to hear, |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Related products

-

On backorder 2-5 Weeks to Arrive

Add to Gift Registry15.99 JOD -

On backorder 2-5 Weeks to Arrive

Add to Gift Registry9.99 JOD -

On backorder 2-5 Weeks to Arrive

Add to Gift Registry9.99 JOD -

On backorder 2-5 Weeks to Arrive

Add to Gift Registry9.99 JOD

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.