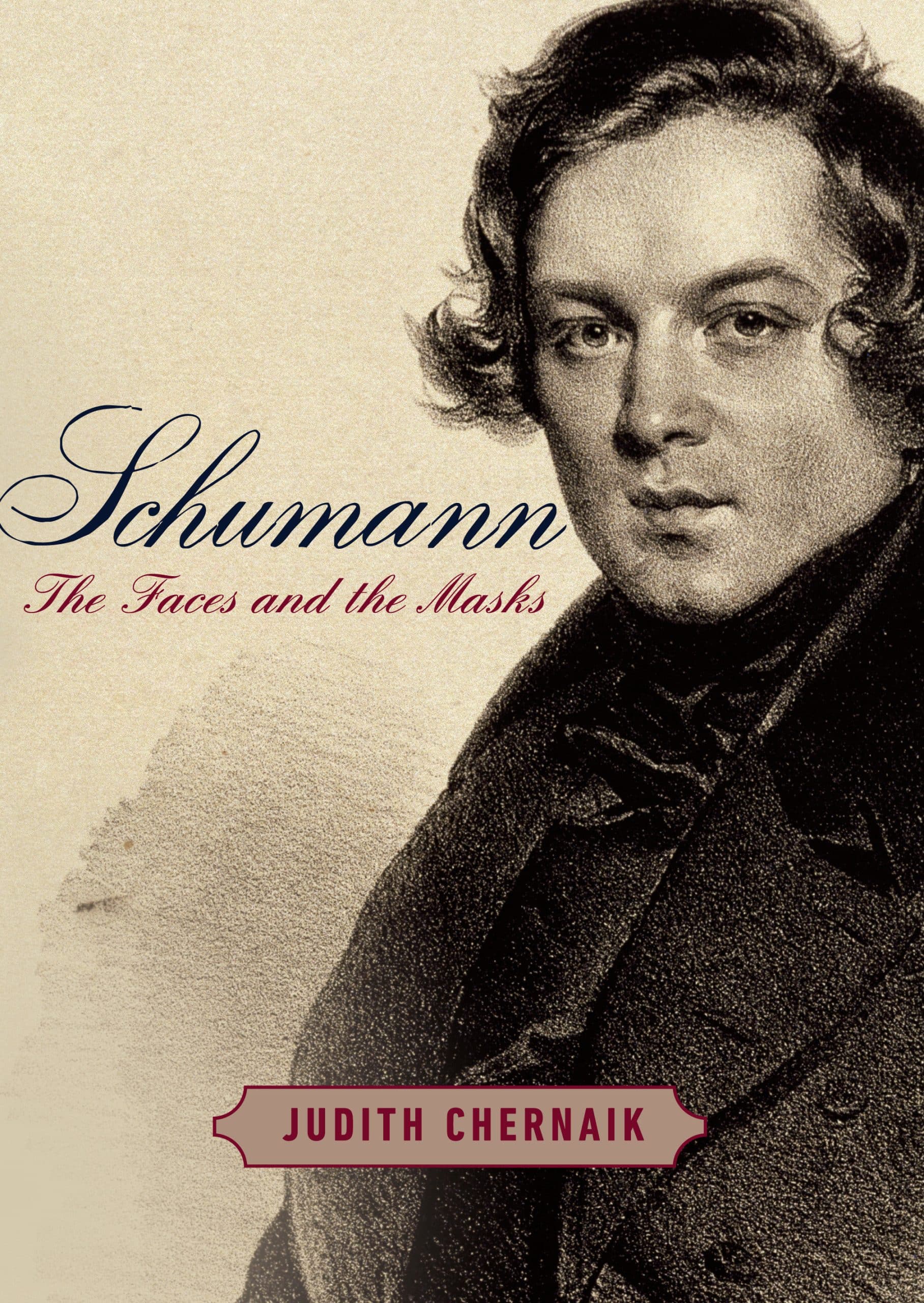

Schumann: The Faces and the Masks

23.00 JOD

Please allow 2 – 5 weeks for delivery of this item

Add to Gift RegistryDescription

Drawing on previously unpublished sources, this groundbreaking biography of Robert Schumann sheds new light on the great composer’s life and work. With the rigorous research of a scholar and the eloquent prose of a novelist, Judith Chernaik takes us into Schumann’s nineteenth-century Romantic milieu, where he wore many “masks” that gave voice to each corner of his soul. The son of a book publisher, he infused his pieces with literary ideas. He was passionately original but worshipped the past: Bach and Beethoven, Shakespeare and Byron. He believed in artistic freedom but struggled with constraints of form. His courtship and marriage to the brilliant pianist Clara Wieck—against her father’s wishes—is one of the great musical love stories of all time. Chernaik freshly explores his troubled relations with fellow composers Mendelssohn and Chopin, and the full medical diary—long withheld—from the Endenich asylum where he spent his final years enables her to look anew at the mystery of his early death. By turns tragic and transcendent, Schumann shows how this extraordinary artist turned his tumultuous life into music that speaks directly—and timelessly—to the heart.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.76 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 3.81 × 16.77 × 24.13 cm |

| PubliCanadanadation City/Country | USA |

| Author(s) | |

| Format | |

| Language | |

| Pages | 368 |

| Publisher | |

| Year Published | 2018-9-18 |

| Imprint | |

| ISBN 10 | 0451494466 |

| About The Author | Judith Chernaik was born and grew up in Brooklyn. She graduated from Cornell University and received a Ph.D. from Yale University. She has taught at Columbia, Tufts, and Queen Mary College in London. Her books include The Lyrics of Shelley and four novels. She has also written a play, and most recently has published essays on Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Chopin in the British academic journal The Musical Times. She and her husband, Warren Chernaik, have been living in London for the last forty years, where she founded Poems on the Underground, which under various names, has since spread all over the world. |

“A generous and tremendously useful resource . . . Without hitting you over the head, Chernaik allows you to feel the core of Schumann’s story. [She] gets the incredible essence of how he offloaded his difficult emotional world onto an imaginary band of alternative identities, partly for survival, partly to fight the philistine world on better terms. . . . Schumann’s spirit comes across as an antidote to all the hate and perverse self-love we are forced to swallow in public affairs, day after day. . . . If you take the time to read Chernaik’s new biography, your life outlook may improve.” —Jeremy Denk, The New York Times Book Review (front cover) “This densely informative biography also provides a comprehensive listening guide to [Schumann’s] music. . . . For Chernaik, the music illuminates the story of a man with ‘more feeling than judgment,’ who emerged as one of the most influential Romantic composers, before a harrowing descent into madness.” —The New Yorker“Chernaik is an enthusiastic student of Schumann’s music and a fine chronicler of his turbulent life. Schumann: The Faces and the Masks is a well-proportioned, highly readable biography for general readers that establishes Schumann as a man thoroughly of his time. The book’s greatest contribution is to situate Schumann in a remarkable fraternity of 19th-century composers.” —Michael O’Donnell, The Wall Street Journal“[Schumann] was an artist of great humanity, a humanity that shines through his musical legacy along with that of his wife, Clara, a brilliant pianist and gifted composer in her own right. Now they have both found a modern biographer, Judith Chernaik, who does them justice with grace and insight. . . . Ms. Chernaik deserves high applause both for reviving an important chapter in musical history and for giving a truly harmonious account of one of the greatest musical love stories of all time.” —Aram Bakshian Jr., The Washington Times “Engrossing . . . A most touching and moving story, beautifully told . . . [Chernaik] understands the poetry of Schumann’s soul and she communicates with quiet urgency the pity of his story and the beauty of his music. If her intention was that by reading this, we’d be inspired to go back to his music with a deeper appreciation, it has worked for me.” —Ysenda Maxtone Graham, Daily Mail“The turbulent life of Robert Schumann, with its final tragic descent into madness, is particularly suitable for biographical treatment. So there’s a distinct bonus in having the experienced literary scholar and novelist Judith Chernaik tackling it so successfully. . . . With Schumann, she has produced an accessible and much needed study expressly aimed at the intelligent general reader rather than the pure subject specialist . . . In her description of Schumann’s difficult and unstable character, [Chernaik] displays great sympathy, sensitivity and psychological insight. . . . Moreover, Chernaik is also musically well-informed, in love with her subject, conversant with the abundant source of materials, some recently discovered, and with such leading authorities as John Daverio and Eric Sams. Thus she is admirably equipped to deal with the way in which a considerable amount of Schumann’s compositions is so closely enmeshed with a wide range of British and German poets and writers. . . . Schumann’s attempted suicide in 1854 and admission to a private mental institution at Endenich are described by Chernaik in great detail with the benefit of the recently published medical diary of its director, and with remarkable empathy for the unimaginable pain he must have suffered as his mind became assailed by terrifying thoughts.” —Andrew Thomson, The Musical Times“Eloquent . . . The book’s strengths lie in its clarity and empathy. . . . Schumann’s personality emerges vividly [in this] deeply moving read.” —Jessica Duchen, BBC Music Magazine “Fascinating . . . Well-documented . . . The author [presents] to us a fully formed Schumann, and we are able to appreciate the richness of his life, expansive range of his music and the humanity of his numerous failures.” —Wylheme H. Ragland, The Decatur Daily“Perhaps it takes a novelist to get inside Schumann’s turbulent imagination: step forward Judith Chernaik, scholar of another pre-eminent early Romantic, Shelley. Fresh insights emerge from access to the composer’s medical records, and consideration of his output as a writer of words as well as music. It’s a tale as gripping as any thriller.” —Pianist“A vivid, sympathetic portrait of emerging genius. . . . Sound on the music, the book is superb on the life. This is the most readable and penetrating biography of this wonderful composer whose life touches modern sensibilities at so many points.” —Stephen Walsh, The Oldie“It would be a strong woman or man who was not shaken by Chernaik’s account of what this sweetest and most vulnerable of men, purveyor of the loveliest, most fantastical and tender of all musical inventions, endured. . . . Schumann’s story has been told from various perspectives, psychoanalytical, cultural, historical. Chernaik has chosen, shrewdly, to tell it through the music, since Schumann’s life is, to a unique degree, incorporated into it—in coded references to himself, to Beethoven, to Bach, to his contemporaries Chopin and Mendelssohn, above all to his wife Clara . . . All of this is ingeniously embedded in his music, even at its most apparently spontaneous and passionate, and Chernaik, a one-woman musical Bletchley Park, has brilliantly decoded it.” —Simon Callow, The Sunday Times (London) “Enthralling . . . Beautifully written, excellently researched, and shot through with love and understanding of her subject . . . [With] a number of fascinating illustrations . . . A most recommendable book.” —Robert Matthew-Walker, Musical Opinion “A sharp, knowing, and complicatedly sympathetic treatment . . . Not only does [Chernaik’s] book feature some of the most passionate appreciations of Schumann’s music ever written in English, but she leaves her readers very specific and very encouraging instructions on how to find every last note of that music for free online . . . The story of the music . . . is expertly intertwined with the well-known details of the weird broken-field obstacle-course that was the man’s life . . . A tremendously persuasive portrait.” —Steve Donoghue, Open Letters Review“An affecting and moving biography . . . Chernaik pays close attention to the music and summons its inimitable combination of romantic ardour, eccentricity and classical craftsmanship in deft prose.” —Ivan Hewett, lead review in The Daily Telegraph “Fast-paced and informative . . . Chernaik vividly brings to life German composer Robert Schumann. Using his personal diaries, letters, and other key archival sources, Chernaik puts his life in a new light while providing an overview of Romanticism in 19th-century Europe.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)“[An] intimate biography . . . [Chernaik], who betrays a close acquaintance with the composer’s oeuvre, offers a very personal take on his life . . . While providing ample discussion of the classical works, [she] eschews technical language and musical notation . . . Highly recommended.” —Herbert E. Shapiro, Library Journal“Altogether outstanding. . . . [Schumann’s] story is oft-told, but Chernaik’s version eclipses its predecessors in two, perhaps three, respects. She has accessed newly released documentation of Schumann’s final illness . . . She fills the book with descriptions of Schumann’s compositions that are more easily followed and more thorough than most recording liner notes and that convincingly relate each piece to Schumann’s life circumstances as well as to his other music . . . The third distinction stems from the fact that Chernaik is also a novelist. She doesn’t get bogged down in data or scholarly one-upmanship, her vocabulary is direct and strong, and she keeps the line of Schumann’s life ever before us.” —Ray Olson, Booklist (starred review)“A guided tour through the life and work of Robert Schumann (1810-1856), a musical genius who viewed the sublime before a decline into syphilitic madness. . . . A sturdy foundation of research and musical knowledge (and love) underlies this inspiring and wrenching account of a man who pursued, captured, and lost.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred review) |

|

| Excerpt From Book | 1 CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH 1810-1830 EARLY YEARS Zwickau, 1810-1827 Schumann’s background was middle-class, provincial, unremarkable. The seeds of his development into a great Romantic composer as well as his later crises, emotional and professional, can be traced in the history preserved in the Robert-Schumann-Haus, a beautifully maintained museum reconstructed on the site of the original family home in the town of Zwickau, in Saxony. He was born on the 8th of June, 1810, the youngest of five children. There were three older brothers and a sister, Emilie, fourteen years older than Robert, who suffered from a severe nervous illness. Robert was petted and adored by his mother, Johanna Christiane, the daughter of Abraham Gottlob Schnabel, the chief surgeon of Zeitz. Johanna was prone to melancholia, and regularly took cures at the famous Bohemian spa of Karlsbad, now Karlovy Vary, fifty-five miles south of Zwickau. She was considered a good singer, with a large repertoire of songs popular at the time. August Schumann, Robert’s father, was the son of a poor country parson from the small town of Endschutz, near Gera. August burned with literary and intellectual ambition but was forced by the family’s poverty to leave school at fourteen. He longed to study at the University of Leipzig, and managed a few months there as an auditor. His early life was a series of frustrations and compromises. He was apprenticed to a local merchant, and later worked as a clerk for a bookseller. He set up his own business to convince Johanna’s father, with whom he lodged, that he would be able to support a wife. Somehow he preserved his literary ambitions. He wrote and published potboilers, romances of knights and monks in the style of gothic novels, and he founded a circulating library. A few years later he moved with his brother to Zwickau and established a publishing and bookselling firm, the Brothers Schumann. Along with lexicons and commercial handbooks, the firm published inexpensive German translations of the classics and a “Pocket Edition of the most eminent English authors,” including novels by Sir Walter Scott and the poems of Lord Byron. August himself translated Byron’s comic verse tale Beppo and Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Byron’s semi-autobiographical verse romance. August Schumann had a special relationship with his gifted son. He encouraged Robert’s literary and musical talents, and was determined to ensure that his son would not have to repeat his own history of frustrated ambition. The boy was always a scribbler, writing poetry, stories, and plays; improvising at the piano, composing ambitious musical scores from an early age. As a fourteen-year-old, Robert helped provide material for his father’s publications, including a Picture Gallery of Famous Men of All Times and Places—perhaps suggesting to Robert that he, too, could one day achieve great things. August had political as well as literary enthusiasms. He sympathized with the ideals of the French Revolution and regarded Napoleon as a liberator until he assumed the imperial crown and embarked on the conquest of Europe. His father’s liberal tastes influenced Robert’s lifelong passion for Byron and his sympathy with the revolutions that swept Europe in 1830 and 1848–1849. August was also a loving and indulgent father. In a letter to his fourteen-year-old son, he writes that he is pleased to learn from Robert’s older brother Eduard that the boy is doing well in his studies; he hopes that he will continue to practice on the fine Streicher piano which his father has recently purchased for him. He appreciates Robert’s concern about his sister, Emilie, whose condition is not improving under the latest treatment. He proposes that Robert might consider visiting his father in Karlsbad, rather than traveling to Dresden with his teacher, the Zwickau organist Gottfried Kuntsch. He ends with fatherly advice: “Now, Robert dear, live properly, remain cheerful, take care of your health, and either travel with Kuntsch to Dresden or come here. In the second case, I shall await you with heartfelt longing.” On an earlier visit to Karlsbad with his mother, Robert heard the great pianist Ignaz Moscheles perform, an inspiration to the youngster, who treasured the program long into his later life. Emilie died in 1825, aged twenty-eight, officially from “a nervous attack,” according to later accounts by drowning herself or throwing herself from a window, in an access of “quiet madness.” A year after Emilie’s death, August Schumann died suddenly, probably suffering a heart attack, though his death was also attributed to “a long-standing severe nervous illness.” He left his wife, three grown sons, who inherited the publishing business, and young Robert, who at sixteen was put under the care of a guardian, Johann Gottlob Rudel. His father’s will provided a yearly annuity on condition that Robert pursue a three-year course of university study—his father’s unfulfilled ambition. A biography of August, published soon after his death, praised his services as an author and publisher, his selfless devotion to family and friends, and his hope that his talented youngest son might pursue his studies unencumbered by the poverty he himself had experienced as a young man. These were the first severe shocks in Robert’s life. In an early diary, he laments having lost two dear human beings, citing one, his father, as “the dearest of all, forever.” One would expect the other loss to be his sister, but the phrase he uses, “one who in a certain view might also be lost to me forever,” could plausibly refer to his romantic attachment to a Zwickau sweetheart, Nanni Petsch, who had rejected him. On the anniversary of his father’s death, he expressed surprise that he did not feel more distressed. On New Year’s Day of 1829, he records reading the “loving letter” of “my wonderful father”—possibly the letter written from Karlsbad to the fourteen-year-old, quoted above. The early losses Robert experienced affected his reactions to the premature deaths of close family and friends during the next decade. His intimate companion the young composer Ludwig Schunke, “a bright star,” died of consumption at twenty-four; his beloved sister-in-law Rosalie died at twenty-nine; his close friend and patron Henriette Voigt died at thirty. He also lost all three of his brothers: Julius at twenty-eight, Eduard at forty, and Carl at forty-seven. Death was always close, in real life as in literature. For his father, and later for Robert, Shakespeare was the first Romantic, and Hamlet’s melancholy was its symbol. Madness real and assumed, suicidal urges, the passionate rejection of the hypocrisy of kings and courtiers—all had great appeal for father and son. Their literary interests were European rather than narrowly German, including the Greek and Roman classics, the works of Dante and Petrarch, as well as the writings of Scott and Byron. Edward Young’s melancholy Night Thoughts was a favorite, as was James Thomson’s The Seasons, in the German translation set to music so memorably by Haydn. While he was still at school, Robert organized a literary circle which met each week to read the plays of Schiller and other works by German writers. Wide-ranging as his literary interests were, Robert also retained from his protected childhood its small-town provincial character. In Zwickau, people knew their neighbors and everything there was to know about their business, their income, their personal trials and scandals. Though he attended the Zwickau grammar school, where he learned French, Greek and Latin, and later had some lessons in English and Italian, Schumann was never at ease in other languages. He reveled in his student holiday travel in northern Italy and Switzerland, but he did not travel extensively in later life, apart from six months in Vienna and a disastrous tour of Russia. His real traveling took place in his mind and his music. At regular intervals throughout his life, Schumann took stock of his achievements and setbacks. These records, meticulously preserved by the family, are a gift to biographers. They are also revealing in ways the writer could not have anticipated. One of the earliest of these documents, composed in Robert’s fifteenth year, describes a cheerful, talented child, eagerly absorbing his school lessons, at eight writing poems to his nine-year-old first love, happiest when wandering alone in the countryside and dreaming. He was already placing himself in the tradition of Goethe’s popular novels, The Sorrows of Young Werther and Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship. He was also a gifted mimic, with a keen comic sense. Several themes of his later life are already apparent in this first of several autobiographies, entitled “My Biography, or the Chief Events of my Life.” I was born in Zwickau on the 8th of June, 1810. Until my third year I was a child like any other; but then, because my mother fell ill with a nervous fever and it was feared she might be contagious, I was sent at first for six weeks to the home of the then Burgomaster Ruppius. The weeks flew by; I loved Frau Ruppius, she was my second mother, in short I remained two and a half years under her truly motherly oversight . . . I still remember well that the night before I was to leave this house, I could not sleep and wept all night long . . . I was a good, handsome child. I learned easily and was at six and a half enrolled in a private school in Freiburg . . . In my seventh year I learned Latin, in my eighth French and Greek, and at nine and a half I entered the fourth class of our lyceum. Already in my eighth year—if one can believe it—I learned to know the art of love: I loved in a truly innocent way the daughter of Superintendent Lorenz, by name Emilie . . . My life then began to be less calm; I was no longer so busy with my school work, although I did not lack talent. What I loved best was to go for walks alone and relieve my heart in nature. After falling in love with young Emilie, who later married his brother Julius, Robert fell in love with Ida Stölzel, for whom he wrote poems, one of which he set to music. His usual pattern thereafter was to fall in love with at least two girls at the same time. His adolescent passions were for Nanni Petsch and Liddy Hempel, one glimpsed at a window, the other sharing a dance—both inspiring an outpouring of longing in his diary. New Year’s Day was always an occasion for Schumann to look back over the past year and to look ahead to the next. His diaries include lists of acquaintances, extracts from his extensive reading, his expenses, and philosophical commentary. Even in his earliest diary he expresses doubt about keeping a record of his life. In true Romantic fashion, he wonders if it might be more authentic to live life intensely than to record it in the cold form of a diary. In the end he embraced the highs and lows of his daily experience and also recorded each day’s events, his love life, real and imagined, and his literary and musical projects, some realized, many abandoned. Addicted to the emotional extremes of Romantic fiction, he took note of his own dreams and nightmares and what we would now call panic attacks. His father would have supported further studies in the arts. But at sixteen, Schumann was subject to the worries of his mother and the guardian appointed to oversee his future. They insisted that he pursue a respectable profession. He agreed to enter the University of Leipzig to study law, hoping to include philosophy and history. It is hard to imagine a less congenial profession for the youth often described as a shy dreamer, lost in his poetic fancies. His brothers were absorbed in running their father’s publishing house in Zwickau and a press in nearby Schneeberg, and they left decisions about Robert’s future to his mother and his guardian. August Schumann’s generous patrimony paid for Robert’s music lessons, his law studies, and his holiday travel. But law it must be, first in Leipzig, and a year later in the romantic city of Heidelberg. |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.