Description

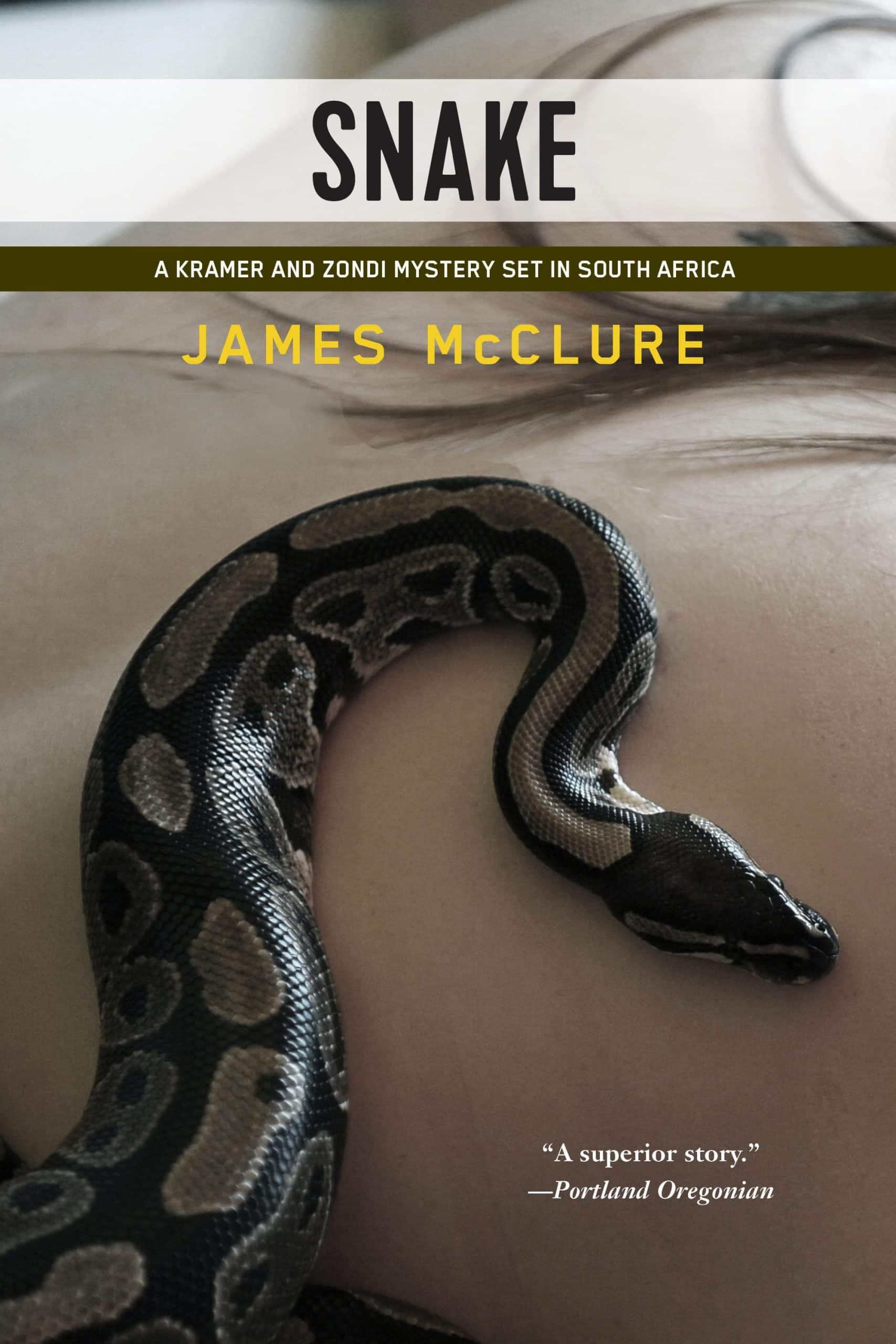

Lieutenant Kramer and Sergeant Zondi have their hands full. On the same day that an adult entertainer known as Eve is found accidentally strangled to death in her dressing room, her pet python wrapped dead around her neck, a beloved candy shop owner named “Lucky” Siyayo is shot to death at his counter in a botched robbery. The detective duo quickly realize neither death is as simple as it looks on the surface: Lucky Siyayo’s cash register was all but empty the day he was murdered, which suddenly throws a whole rash of fatal neighborhood robberies into perspective—were none of them robberies at all? It becomes clear a killer is on the loose, but Zondi and Kramer must figure out what the killer is after. Meanwhile, postmortem analysis reveals that Eve didn’t die at the time her ex-boss had stated he’d discovered her body; the more Kramer picks the circumstances apart, the less they make sense. With two very different sets of crimes to solve, Kramer and Zondi set off on treks that take them all over town, from the poorer villages to the sleazy dressing rooms of con artists and pimps to gorgeous steop of the South African countryside in another surefire investigation full of both stirring observations of Apartheid and plenty of mischief. Only one thing is for sure—no one is getting to take his day off this week!

Additional information

| Weight | 0.28 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 1.55 × 12.7 × 19 cm |

| PubliCanadation City/Country | USA |

| Author(s) | |

| Format | |

| language1 | |

| Pages | 224 |

| Publisher | |

| Year Published | 2011-8-9 |

| Imprint | |

| ISBN 10 | 1569479682 |

| About The Author | James McClure (1939-2006) was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he worked as a photographer and then a teacher before becoming a crime reporter. He published eight wildly successful books in the Kramer and Zondi series during his lifetime. The first two books in the series, The Steam Pig and The Caterpillar Cop, are available in paperback from Soho Crime. |

Praise for James McClure:"The pace is fast, the solution ingenious. Above all, however, is the author's extraordinary naturalistic style. He is that rarity—a sensitive writer who can carry his point without forcing."—The New York Times Book Review"A revealing picture of the hate and sickness of the apartheid society of South Africa."—Washington Post"So artfully conceived as to engender cheers…. A memorable mystery."—Los Angeles Times"This well-plotted, well-written murder mystery is exceptional … sometimes grim, sometimes sourly comic, always shocking."—The Atlantic"Soho completes its reprinting of one of the finest police series to begin in the 1970s, James McClure's eight books about Tromp Kramer and Mickey Zondi, a South African biracial detective team in the days of Apartheid." —Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine"A superior story by any yardstick."—Portland Oregonian |

|

| Excerpt From Book | EVE DEFIED DEATH twice nightly, except on Sundays.Sunday had just begun when there was a soft rap of knuckleson the dressing room door.“Go away,” she lisped, resentful.Monday through Friday, she did a show at eleven and a showat one. The first timed to catch and hold the after-the-moviescrowd, the second to prime them for their beds, titillated andeager to return for more. Come Saturday, however, both showshad to be over before the laws regarding public drinking andentertainment on the South African sabbath came into effect.Making a total of twelve hours in all, but it was tiring, stressfulwork.So when her week ended on the stroke of midnight,she gladly turned into a pumpkin. Her taut orange skinand round face were just right for one, for a do-nothing,think-nothing, vegetating pumpkin which—once she hadremoved her small top plate—smiled gap-toothed into themirror like a Halloween lantern. Nobody paid her to bepretty in private.The knuckles rapped again.Her smile quite disappeared. She replaced the plate andtwisted round on her stool.“Go on, voetsak you!” she called out with cold clarity. “Leavea girl in peace.”A shuffle of feet moving closer to the door.“Eve?”“That you, baby?”“Can I see you for a minute, please?”She had heard that one before, yet reached round for hergown and hitched it over her shoulders.“You can see me from there,” she said, opening the door acrack.He really was a baby, a great big baby who just wantedmothering—and, like a baby, was liable to kick up a terriblerumpus unless he got it.“I wanted—do you think it’s a hell of a cheek?”“I’m listening.”She was also trying to work out what he was up to thistime.“Well,” he said diffidently, bringing out a hand from behindhim and showing her the champagne bottle grasped in it bythe neck.“Oh, ja?”He offered her the bottle.“It’s all right,” he said. “I don’t have to come in.”She was obviously meant just to take it. But, what withclutching her gown across her bosom, she hadn’t a hand tospare. And besides, that would have seemed mean.“For me?”“Please.”“Who gave you this idea? An old film?”“I—I just thought of it.”“Oh, ja?”“It’s been a wonderful week.”“So you acted on impulse, hey?”He smiled broadly, somehow flattered.“That’s me, Eve. I just wanted to—well—thank you andthat. All right?”Her instincts had cried wolf so often it had become impossibleto make a fair assessment—one fair to him as well as toherself.“You’re on your own?”“Sorry?”“It’s a big bottle.”“We don’t have to—”“Look,” she said. “Just you wait a minute and I’ll see.”She glanced down at his patent leather shoes. Neither triedto wedge the door. So she closed it gently and looked across intothe big mirror. Her reflection was never much real company,and on this, her last night in Trekkersburg, the truth was shedid feel a bit flat and lonely. On top of which, the spontaneityof the gesture had touched her. Nobody’d ever brought herchampagne before, and she was close to a mood that hintednobody else ever would.“Okay, then?” she mouthed silently.Her reflection raised an eyebrow that quivered, queryingher judgment on the basis of the known facts—such as that bigbabies were always easy to kick out once she had had enoughof them. Then it slowly regained its penciled symmetry. Sheshrugged. It shrugged.“Ach, that’s it,” she said, fastening the belt of her gownproperly.Then she lifted a large wicker basket onto the divan andundid the leather straps. From inside it she took a python,roughly five feet long and almost two inches thick in themiddle, beautifully patterned with light-brown shapes likeround leaves, and draped him over her shoulders. The weightwas that of a protective pair of arms.He did a double take. It was usually the last she saw of theones who weren’t sincere.“You don’t mind?” she said. “Clint gets so restless aftera show if I put him straight back in his basket. He’ll be good.”His eyes gleamed. She took this for amusement, then was notsure, but by then he had politely sidled round her to take up aposition beside where her street clothes hung from a hook.Pressing the door closed behind her, she made certain itwould stay shut against any other callers, and then pointed tothe stool.“Like a seat?”“No, I’m fine, thanks—thank you very much.”“Well, I’ve been on my feet long enough for one day,” shesaid, sitting down. “Glamorous, isn’t it?”She was getting in another dig about the way she had tolive. The dressing room had three walls showing their brickworkthrough a thin coat of whitewash, a fourth wall madeof bulging chipboard, an uneven cement floor, and a ceilingall stained and saggy like old underwear. As for furnishings,there was the blotchy mirror stuck crookedly to the wallopposite the door, a row of wire coat hangers on hooks fora wardrobe, a junkshop dressing table, a grass mat, a divan,and a wash basin with bad breath—plus, of course, the stoolshe was perched on, which gave you splinters if you weren’tcareful. No window at all.“You are a bit untidy, Eve.”That was true, but one of those annoying surface remarksall the same.“I bet where you live is worth keeping nice!” she said.“That’s a bit nasty! You don’t really expect what film starsare given, do you? Although, mind, I’m not saying you’re notworth it!”“You trying to butter me up?”“How?” he asked, in that abruptly innocent way of his.“Ach, forget it There’s a glass and a mug by the basin.”“I should have thought to bring some!”“You’ll have to wash them. I use tissues for drying.Here—catch.”He fumbled his catch and dropped the box. Then made adreadful clatter with the things in the basin. It gave her a certainamount of unkindly pleasure to see him doing such work.God, but he had a soft life.The cork came out of the bottle with a sharp report. Snakeshave no means of picking up airborne sound, but her suddenflinch caused the python to contract his coils, and she had tocoax him out a little in order to stay comfortable. Very soon,once she was sure everything was as before, Clint could goback in his basket.She was handed the more ladylike glass, filled to within asplash of the brim.“To you, Eve!”“Ta. And to you.”They drank.“Is that your proper name? Eve?”“Can you think of a better?”He dimpled and shook his head.“Put it this way,” she added, finding she had almost downedthe lot. “It’s not what they’ll put on my tombstone.”Why that sent a shudder through her as she said it was thebooze for you. She was young, fit and healthy, and never reallydid anything dangerous.“Goose walk over?” he asked, grinning.“Pardon?”“Too late! Not bad stuff—didn’t know we had decent bubblyhere. You and I should have started earlier on it.”He was beginning to assert himself. Beginning to feel moreat home, perhaps, than he ever did in his own place, from whatshe had heard of it. The woman sounded a right bitch. Poorlittle chap.“The whitewash will come off on your jacket.”“Oh, don’t worry, I’ve got more—this isn’t my onlyone.”She had noticed; a different suit practically every night—asif less-regular customers would ever notice.“But let’s talk about you for a change,” he said. “Why notdo more with yourself? Take this act to Lesotho and go thewhole hog?”“In front of natives? That’ll be the day! Besides, what’s this‘nude’ rubbish? I thought you were the one who appreciatedthe psychological way I use—”“Please, please. I was only wanting things better for you,the sort of—er—contracts you really deserve. You’re a realartist and it’s high time you realized it! What’s Trekkersburg?There’s a limit here on what it could ever do for you. And, Iagree, the same applies really to Maseru. But have you everthought of London? Hamburg? Vegas?”“I see—and you could be my manager?”“Why’s this making you angry?”“Ach, because every five minutes some bugger tries that lotof smoothie talk on me. I’m sick and tired of it!”“Is that how it sounded?”“Yes!”“Then I’m sorry, really sorry to have said the wrong thing,although I promise you that I meant it. Come on, have anotherdrop.”Typical. Do what you like, say sorry, and everything was fineagain. All men stayed babies, when you came to think of it. Bityour finger and then went goo-goo. She was saddened but notsurprised to find it all turning sour. Such was life.But at least the champagne had not lost its sweetness. It musthave cost a bomb retail. Sweet and tickly and gone in an instantdown into a tummy kept empty for the more difficult positions.And from there, moving on to make her sore limbs feel betterthan a warm bath would have done, which the boardinghousedidn’t seem to own anyway, and her head so pleasantly muzzythat the bare light no longer hurt her eyes.She let him refill her glass.“There—watch it doesn’t spill! Can’t let any go to waste. Youknow what I’ve decided to do? Take a little holiday on my own.”Plan B was being put into operation.“Oh, ja?”“Do you ever take a holiday?”“Sometimes. When Clint has eaten a big meal.”His eyes became fixed on the python.“Clint doesn’t like being stared at,” she said, then finishedthe line from her family show: “He thinks you’re trying tohypnotize him.”He laughed loudly. “What does he feel like, Eve?”“Smooth and nice—not slimy.”“How strong is he, really?”“One his size can kill a duiker—even a buck much bigger.Touch him.”His free hand went into his pocket, and he raised the otherto show it held the mug. Baby didn’t want to.“What’s the matter—do you want your mummy?”“That isn’t like you, Eve,” he said, very hurt.Then the fingers, with their bitten-down nails, reached outand just dabbed at the scales. Clint tried to escape from hershoulders. She pulled him back“Not so cold,” he said. “Super.”“Room temperature.”“I see. And you feed him on. . . ?”“Guinea pigs.”“Dead or alive?”“I just chuck them in his basket. Sometimes nothing happensfor hours, then you hear the squeaking. Only I don’t givehim them often or he’d get even lazier. Wouldn’t you, you oldbastard?”And she held the python’s head with deceptive firmness asshe nuzzled noses with him.“Can I see him eat one?”“Not feeding time.”“Please.”That was another of his magic words, like sorry.“I’ll pay for it. Clint can have one on the house, so tospeak.”I’ll pay.“If you can tear yourself away from this club some night,come down and see us in Durban. I’ve got a spitting cobra thateats when he likes.”“Come off it, Eve! You know you’re the real attraction!”Double meanings next—he was doing well.“Oh, ja? I fascinate you, do I?”“Well, in a way, yes—yes, you do.”“And why?”He shrugged, looking more thoughtful than she hadexpected.“Because I play with snakes?”“That might have been it to begin with—I thought it wouldbe interesting talking to you—but I’ve also had this funnyfeeling. . . .”His sentence seemed to quite genuinely tail off, and his eyesleft her as he frowned and bit his thumbnail. There was a jobfor him in show business as well, no doubt of that.“My God, you’re not going to sulk, are you?” she said.“Me?”And he laughed softly, topping up her glass again, returningit to her with a flourish. The professional charm was switchedon and off so suddenly you could almost hear the click.“What exactly did you want to thank me for? I get paid fordoing it, don’t I?”“You. Your show. All of it.”“Turns you on?”“Does someone I know.”“Hey! This is something new! Don’t tell me you’ve actuallygot a girlfriend hidden someplace?”“Oh, she’s not here. She’s—she’s on holiday.”“Ach, I realize that she isn’t standing outside the door, man. Iwas just surprised because, after what you’ve told me, it hardlyseems likely that your old battleship would approve.”“I never take her home with me,” he said solemnly.“Hell! As bad as that, is it?”He laughed longer than she did.Sick, that, him wanting to watch Clint gobble up a guineapig. Things were now taking a little time to sink in, which wasalso nice. She’d never watched, even though it was just a factof life like any other Clint had to eat, but nobody had to seehim do it. Most people would think the same way she did, sohe couldn’t be all that typical. He was weird.“Are you weird?” she asked, sipping a little more.“What a question!”“I was thinking about you wanting to gawk at Clint havinghis num-nums.”“I’d just be interested. What’s weird in that?”Nothing, when you thought about how excited the samething would make small kids. If they saw it happen in agame reserve, they’d love it and show no pity or otherinside things. If the snake came for them, that would be adifferent matter, but their fear—like his—was an outsideone. And she saw that happening all around her every nightto grownups.“What are you dreaming about?” he asked, making his voicefriendly but not quite covering his nervousness.“I was thinking.”“Is it catching?”As if able to read her mind, he reached out again to touchthe python.“Not too close to his head,” she warned.“Pythons don’t bite.”“Who told you that?”“But they’re not poisonous.”“Blood poisoning. You can catch blood poisoning from histeeth—they’re dirty.”He winced. “Can’t it go in the basket?”“Just now.”So the girlfriend was away. Oh, yes, that began to explaina few things. Such as a bottle of champagne so big that twopeople could get very drunk on it. A bottle that had probablybeen shown to quite a few eyes in the club earlier on, and therehad also probably been jokes about her. Even a few coarse betslaid. It was becoming clearer.“You haven’t been to my dressing room before,” she said.“I know. So?”“It wasn’t so private at the table.”“What—what are you hinting at?”Quick as a flash, he was. Look at the innocent smile.“You told your friends you were coming here?”“What?”“Friends, pals, closest buddies.”He frowned, as if he didn’t understand.“Am I right?”“I don’t really have any,” he said. “Certainly nobody I’d tellthis to.”Tell this to.She hesitated. This was the moment to kick him out. Yet shecould still be the loser: he could go back and make up somethingfilthy for his cronies that would have them all outside,banging on the door, waving bottles. Or waiting for her in thealley, or tailing her back to the boardinghouse. The bugger of itwas she had allowed him to stay too long already, and so kickinghim out wasn’t going to solve anything. If only there was someway she could stop him from telling anyone stories that couldhurt her—make him run off home with his tail between hislegs. If only. . . .There was a way! And by the time she had finished withhim, he wouldn’t even want to think about it, let alone talk.She knew men. |

| series |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.