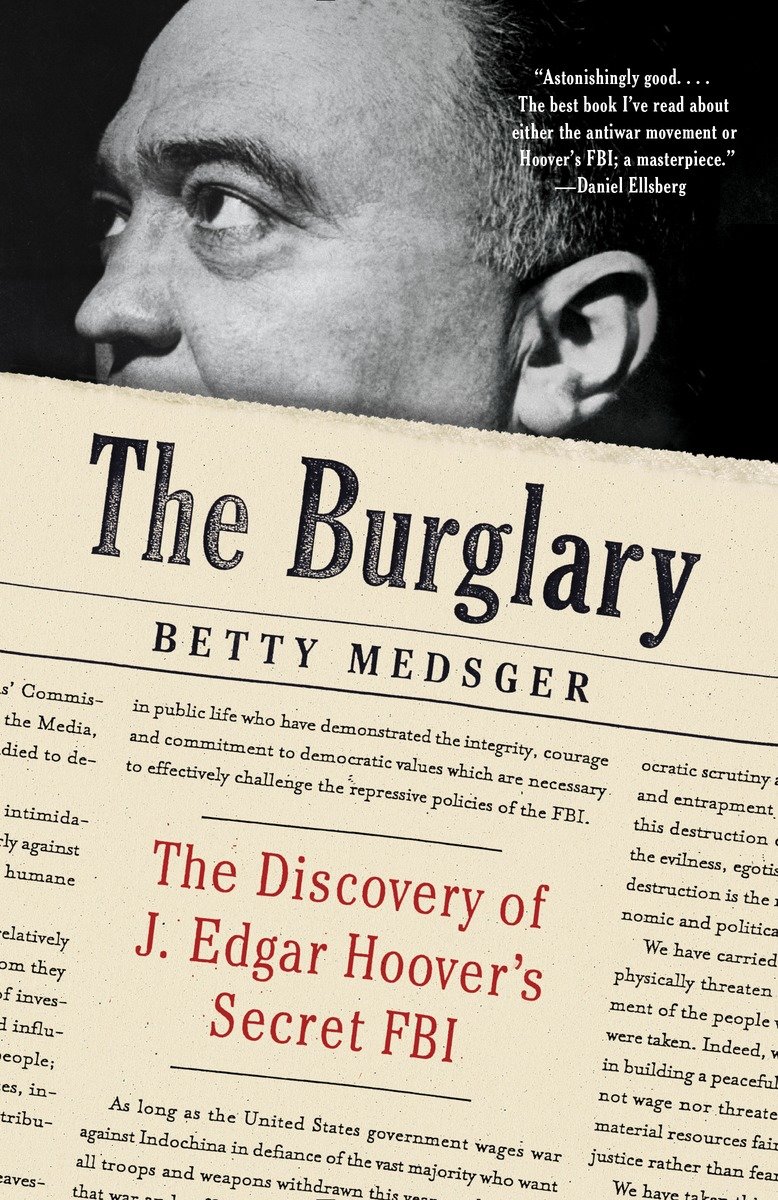

The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI

14.00 JOD

Please allow 2 – 5 weeks for delivery of this item

Add to Gift RegistryDescription

INVESTIGATIVE REPORTERS & EDITORS (IRE) BOOK AWARD WINNER • The story of the history-changing break-in at the FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, by a group of unlikely activists—quiet, ordinary, hardworking Americans—that made clear the shocking truth that J. Edgar Hoover had created and was operating, in violation of the U.S. Constitution, his own shadow Bureau of Investigation.“Impeccably researched, elegantly presented, engaging.”—David Oshinsky, New York Times Book Review • “Riveting and extremely readable. Relevant to today’s debates over national security, privacy, and the leaking of government secrets to journalists.”—The Huffington PostIt begins in 1971 in an America being split apart by the Vietnam War . . . A small group of activists set out to use a more active, but nonviolent, method of civil disobedience to provide hard evidence once and for all that the government was operating outside the laws of the land. The would-be burglars—nonpro’s—were ordinary people leading lives of purpose: a professor of religion and former freedom rider; a day-care director; a physicist; a cab driver; an antiwar activist, a lock picker; a graduate student haunted by members of her family lost to the Holocaust and the passivity of German civilians under Nazi rule.Betty Medsger’s extraordinary book re-creates in resonant detail how this group scouted out the low-security FBI building in a small town just west of Philadelphia, taking into consideration every possible factor, and how they planned the break-in for the night of the long-anticipated boxing match between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali, knowing that all would be fixated on their televisions and radios.Medsger writes that the burglars removed all of the FBI files and released them to various journalists and members of Congress, soon upending the public’s perception of the inviolate head of the Bureau and paving the way for the first overhaul of the FBI since Hoover became its director in 1924. And we see how the release of the FBI files to the press set the stage for the sensational release three months later, by Daniel Ellsberg, of the top-secret, seven-thousand-page Pentagon study on U.S. decision-making regarding the Vietnam War, which became known as the Pentagon Papers.The Burglary is an important and gripping book, a portrait of the potential power of nonviolent resistance and the destructive power of excessive government secrecy and spying.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.52 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 3.31 × 13.16 × 20.22 cm |

| PubliCanadation City/Country | USA |

| book-author1 | |

| Format | Paperback |

| Language | |

| Pages | 624 |

| Publisher | |

| Year Published | 2014-10-7 |

| Imprint | |

| ISBN 10 | 0804173664 |

| About The Author | Betty Medsger first wrote about the Media files as a reporter at The Washington Post in 1971. She is a founding member of Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) and founder of the Center for Integration and Improvement of Journalism at San Francisco State University, where she was chair of the Department of Journalism. She is the author of Women at Work, Framed: The New Right Attack of Chief Justice Rose Bird and the Courts and Winds of Change: Changes Confronting Journalism Education. She lives in New York with her husband, John T. Racanelli. |

One of the Best Books of the Year, St. Louis Post-DispatchInvestigative Reporters & Editors (IRE) Book Award Winner“Rich and valuable.”—David J. Garrow, The Washington Post “Impeccably researched, elegantly presented, engaging…For those seeking a particularly egregious example of what can happen when secrecy gets out of hand, The Burglary is a natural place to begin.”—David Oshinsky, New York Times Book Review“A cinematic account . . . By turns narrative and expository, The Burglary provides ample historical context, makes telling connections and brings out surprising coincidences . . . makes a powerful argument for moral acts of whistle-blowing in the absence of government action.”—San Francisco Chronicle“An important work, the definitive treatment of an unprecedented and largely forgotten ‘act of resistance’ that revealed shocking official criminality in postwar America. One need not endorse break-ins as a form of protest to welcome this deeply researched account of the burglary at Media. Ms. Medsger’s reporting skill and lifelong determination enabled her to do what Hoover’s FBI could not: solve the crime and answer to history.”—The Wall Street Journal “Riveting and extremely readable. Not just an in-depth look at a moment in history, The Burglary is also extremely relevant to today's debates over national security, privacy, and the leaking of government secrets to journalists.”—The Huffington Post“Astonishingly good, marvelously written…the best book I've read about either the antiwar movement or Hoover's FBI; a masterpiece.”—Daniel Ellsberg"Ordinary people have the courage and community to defeat the most powerful and punitive of institutions — including the FBI. That's the unbelievable-but-true story told by Better Medsger, the only writer these long term and brave co-conspirators trusted to tell it. The Burglary will keep you on the edge of your seat — right up until you stand up and cheer!" —Gloria Steinem “Beautifully told…The Burglary vividly recreates the atmosphere of the era.”—Aryeh Neier, The New York Review of Books“The break-in at the FBI offices in Media, Pennsylvania changed history. It began to undermine J. Edgar Hoover’s invulnerability. Betty Medsger writes a gripping story about the burglary, the burglars, and the FBI’s fervid but fruitless efforts to catch them. Her story of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI (and today’s NSA) teaches the dangers of secret power.”—Frederick A. O. Schwarz, Jr., former Chief Counsel to the U.S. Senate’s Church Committee investigating America’s intelligence agencies and author of the forthcoming Unchecked and Unbalanced "I stayed up until 3 a.m. today. Now it's nearly 6 p.m. I have not done laundry, paid my bills or washed the dishes. I can't put the damn book down. What a triumphant piece of work!"—Rita Henley Jensen, founder and editor-in-chief, Women's eNews “A riveting account of a little-known burglary that transformed American politics. Medsger's carefully documented findings underscore how secrecy enabled FBI officials to undermine a political system based on the rule of law and accountability. This is a masterful book, a thriller.”—Athan Theoharis, author of Abuse of Power: How Cold War Surveillance and Secrecy Policy Shaped the Response to 9/11 “In The Burglary, Betty Medsger solves the decades-long mystery the FBI never could: who broke into an FBI office in 1971 and exposed the Bureau’s secret program to stifle dissent? An astonishing and improbable tale of anonymous American heroes who risked their own freedom to secure ours, triggering the first attempt to subject our intelligence agencies to democratic controls. The book couldn’t be more timely given the current furor over a new generation of domestic spying.”—Michael German, former covert counterterrorism FBI agent “A masterpiece of investigative reporting. As a writer, I admire the way Betty Medgser has explored every angle of this truly extraordinary piece of history and told it with the compelling tension of a detective story. As an American, I’m grateful to know at last the identities of this improbable crew of brilliant whistle-blowers who are true national heroes. As someone appalled by recent revelations of out-of-control NSA spying, I’m reminded that it has all happened before, and that then, as now, it took rare courage to expose it. This brave group of friends were the Edward Snowdens of their time.” —Adam Hochschild, author of King Leopold’s Ghost“Extraordinary . . . It is impossible to read Betty Medsger’s book without drifting into comparisons between then—when J. Edgar Hoover was the director of the FBI—and now—when Gen. Keith Alexander was the director of the NSA.”—Firedoglake Book Salon“Reading [The Burglary] might make you feel . . . like taking a crowbar to the offices of the NSA . . . Gripping . . . [The] timing couldn’t be better.”—Biographile“There is joy and fun—and lots of law breaking—in Betty Medsger's book. The Burglary answers the question long asked and speculated about within Catholic Left, as well as law and order, circles: Who did the 1971 Media, Pa., FBI break-in . . . Fast paced, fascinating . . . studded with timely insights for today's WikiLeaks, intelligence breaches and NSA scandals.”—Frida Berrigan, Waging Nonviolence |

|

| Excerpt From Book | In late 1970, William Davidon, a mild–mannered physics professor at Haverford College, privately asked a few people this question:“What do you think of burglarizing an FBI office?”Even in that time of passionate resistance against the war in Vietnam that included break–ins at draft boards, his question was startling. What, besides arrests and lengthy prison sentences, could result from breaking into an FBI office? The bureau and its legendary director, J. Edgar Hoover, had been revered by Americans and considered paragons of integrity for the nearly half century he had been director.Who would dare to think they could break into an FBI office? Surely the offices of the most powerful law enforcement agency in the country would be as secure as Fort Knox. Just talking about the possibility seemed dangerous.But Davidon, with great reluctance, had decided that burglarizing an FBI office might be the only way to confront what he considered an emergency: the likelihood that the government, through the FBI, was spying on Americans and suppressing their cherished constitutional right to dissent. If that was true, he thought, it was a crime against democracy—-a crime that must be stopped.The odds were very low that such an act of resistance could possibly succeed against the law enforcement agency headed by this man who held so much power. Nicholas Katzenbach, who as attorney general was Hoover’s boss, had resigned in 1966 because of Hoover’s resentment over being told by Katzenbach to manage the bureau within the law. The director’s power was unique among all national officials, said Katzenbach. He “ruled the FBI with a combination of discipline and fear and was capable of acting in an excessively arbitrary way. No one dared object. . . . The FBI was a principality with absolutely secure borders, in Hoover’s view.” At the same time, he said, “There was no man better known or more admired by the general public than J. Edgar Hoover.”Such was the power and reputation of the official whose borders and files Davidon was considering invading. He knew Hoover was very powerful, but he didn’t know—-nor could anyone outside the bureau have known—-how harshly he ruled it and how he protected the bureau from having its illegal practices exposed. Katzenbach believed that Hoover or one of the director’s top aides had even forged Katzenbach’s signature in order to make it appear that the attorney general had given permission for the FBI to plant an electronic surveillance device, a bug, in civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.’s New York hotel room. Despite what appeared to be his signature on the memorandum, Katzenbach was certain he never approved such a procedure, which he considered the “worst possible invasion of privacy.” Hoover’s sensitivity to criticism, Katzenbach said when he testified in December 1975 before the committee then conducting the first congressional investigation of the FBI, “is almost impossible to overestimate. . . . It went far beyond the bounds of natural resentment. . . . The most casual statement, the most strained implication, was sufficient cause for Mr. Hoover to write a memorandum to the attorney general complaining about the criticism, explaining why it was unjustified, and impugning the integrity of its author.“In a very real sense,” Katzenbach testified, “there was no greater crime in Mr. Hoover’s eyes than public criticism of the bureau.”A congressional investigation of the FBI during Mr. Hoover’s lifetime, Katzenbach said, would have been utterly impossible. “Mr. Hoover would have vigorously resisted. . . . He would have asserted that the investigation was unnecessary, unwise and politically motivated. At worst, he would have denounced the investigation as undermining law and order and inspired by Communist ideology. No one [in Congress] risked that confrontation during his lifetime.”Said Katzenbach, “Absent strong and unequivocal proof of the greatest impropriety on the part of the director, no attorney general could have conceived that he could possibly win a fight with Mr. Hoover in the eyes of the public, the Congress or the President. Moreover, to the extent proof of any such impropriety existed, it would almost by definition have been in the Bureau’s possession and control, unreachable except with Bureau cooperation.” Five years before Katzenbach made that public assertion, Davidon was planning to do something that had never been done—-obtain official FBI information that was otherwise unreachable. Davidon had given a lot of thought to the question before he asked it—-“What do you think of burglarizing an FBI office?” If anyone else had asked that question of the nine people he approached, probably each of them would have swiftly ended the conversation. Because it was Davidon, they took it seriously and kept listening despite being shocked. They trusted him. They knew he wasn’t reckless, and they knew he believed in protest that was effective, that could lead to results. Each of them respected him so much they thought that if they ever engaged in high–risk resistance, he was one of the few people they would want as partner and leader when the stakes were high. So they listened carefully.Some of them wrestled with the implications of his question for several days. Two said yes immediately. Only one of them, a philosophy professor, turned him down. Eight agreed with him that, repugnant as burglary was as a method of resistance, it might be the only way to find documentary evidence that would answer important questions about the FBI that no journalist or government official responsible for the FBI had dared to ask in the past or, they concluded, was likely to ask now or in the future. All of them were passionate opponents of the Vietnam War and passionate opponents of the suppression of dissent. Davidon and the eight people who said yes in response to his question met as a group for the first time shortly before Christmas 1970 and chose their name, the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI. The name summed up their goal: In the absence of official oversight of this powerful law enforcement and intelligence agency, they, acting voluntarily on behalf of American citizens, would attempt to steal and make public FBI files in an effort to determine if the FBI was destroying dissent. They thought the name sounded dignified, like that of an official commission that should have been appointed years earlier by a president, an attorney general, or Congress.Agreeing to break in only if it could be done without violating their deep commitment to nonviolent resistance, they concentrated on developing the skills necessary to conduct an unarmed burglary of the office. Beginning in January 1971, most weekday evenings, after they meticulously cased the area near the targeted FBI office for at least three hours, they drove to the Germantown neighborhood in northwest Philadelphia to the home of John and Bonnie Raines, a young couple who had agreed to participate. There, late at night in a room in the back of the Raines’ third–floor attic, they trained themselves as amateur burglars and planned the break–in. They discussed the discoveries they had made during casing and how to work around serious obstacles they had determined could not be eliminated, such as the fact that security guards stood twenty–four hours a day behind the glass front door of the Delaware County Courthouse constantly monitoring an area that included the nearby entrance to the building the burglars would enter, as well as the windows of the FBI office. Just a few days before the burglary, another critical problem developed over which they had no control: One of the burglars abandoned the group, with full knowledge of what they were going to do. He later threatened to turn them in.On the night of March 8, 1971, the eight burglars carried out their plan. Under the cover of darkness and the crackling sounds in nearly every home and bar of continuous news about the Muhammad Ali–-Joe Frazier world heavyweight championship boxing match taking place that evening at New York’s Madison Square Garden and being watched on television throughout the world, the burglars broke into the FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, a sleepy town southwest of Philadelphia. At first, their break–in plan failed. The locks were much more difficult to pick than expected. Frustrated, the newly minted locksmith in the group found a pay phone, called the other burglars as they waited at the nearby motel room that served as the group’s staging area, and told them the burglary might have to be called off. Michael German, a former FBI agent who conducted undercover FBI operations for sixteen years before joining the staff of the American Civil Liberties Union in 2006, said he has often wondered how the Media burglars knew which files to take. “How did they know,” for instance, he asked, “where the political spying files would be?” German said he has always assumed—-and has talked to other agents who made the same assumption—-that because it would have been impossible for an outsider to know where particular files were, the Media burglary must have been an inside job carried out by disgruntled FBI agents familiar with the files. But the burglars had found a foolproof solution to the problem of which files to take: They removed every file in the office. That’s why, as they drove away from Media in their getaway cars late that night, they had no idea what they had stolen. For all they knew, they might have just risked spending many years in prison for a trove of blank bureaucratic forms.Within an hour of opening the suitcases they had stuffed with FBI files, they knew their risk was not in vain. They found a document that would shock even hardened Washington observers when it became public two weeks later.The files stolen by the burglars that night in Media revealed the truth and destroyed the myths about Hoover and the institution he had built since he became its director in 1924. Contrary to the official propaganda that had been released continuously for decades by the FBI’s Crime Records Division—-the bureau’s purposely misnamed public relations operation—-Hoover had distorted the mission of one of the most powerful and most venerated institutions in the country.The Media files revealed that there were two FBIs—-the public FBI Americans revered as their protector from crime, arbiter of values, and defender of citizens’ liberties, and the secret FBI. This FBI, known until the Media burglary only to people inside the bureau, usurped citizens’ liberties, treated black citizens as if they were a danger to society, and used deception, disinformation, and violence as tools to harass, damage, and—-most important—-silence people whose political opinions the director opposed. Instead of being a paragon of law and order and integrity, Hoover’s secret FBI was a lawless and unprincipled arm of the bureau that, as Davidon had feared, suppressed the dissent of Americans. To the embarrassment and frustration of agents who privately opposed this interpretation of the bureau’s mission, agents and informers were required to be outlaws. Blackmail and burglary were favorite tools in the secret FBI. Agents and informers were ordered to spy on—-and create ongoing files on—-the private lives, including the sexual activities, of the nation’s highest officials and other powerful people.Electoral politics were manipulated to defeat candidates the director did not like. Even mild dissent, in the eyes of the FBI, could make an American worthy of being spied on and placed in an ongoing FBI file, sometimes for decades. As the authors of The Lawless State wrote in 1976, the FBI “has operated on a theory of subversion that assumes that people cannot be trusted to choose among political ideas. The FBI has assumed the duty to protect the public by placing it under surveillance.”Until the Media burglary, this extraordinary situation—-a secret FBI operating under principles that were the antithesis of both democracy and good law enforcement—-thrived near the top of the federal government for nearly half a century, affecting the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans. The few officials who were aware of some aspects of the secret FBI silently tolerated the situation for various reasons, including fear of the director’s power to destroy the reputation of anyone who raised questions about his operations.When these operations became known as a result of the burglary, the foundations of the FBI were shaken. The significant impact of the burglary was both long–term and immediate. As soon as the files became public, Americans’ views of the FBI started to change. Mark Felt—-the future Deep Throat of Watergate fame, who at the time of the burglary was chief of bureau inspections and very close to Hoover—-wrote in 1979 that the Media burglars’ disclosures “damaged the FBI’s image, possibly forever, in the minds of many Americans.” Ironically, the burglary would not have been possible if Felt had not refused in the fall of 1970 a request to increase security at the Media office.This historic act of resistance—-perhaps the most powerful single act of nonviolent resistance in American history—-ignited the first public debate on the proper role of intelligence agencies in a democratic society. Perceptions of the bureau evolved from adulation to criticism and then to a consensus that the FBI and other intelligence agencies must never again be permitted to be lawless and unaccountable. By 1975, the revelations led to the first congressional investigations of the FBI and other intelligence agencies and then to the establishment of congressional oversight of those agencies.The writers of every history of Hoover or the bureau since the burglary have noted its significant impact. Sanford J. Ungar, author in 1976 of the first history of the bureau published after the burglary, FBI: An Uncensored Look Behind the Walls, wrote, “The Media documents . . . gave an extraordinary picture of some of the Bureau’s domestic intelligence activities. . . . Judged by any standard, the documents . . . show an almost incredible preoccupation with the activities of black organizations and leaders, both on campuses and in the cities. . . . The overall impact of the documents could not be denied or explained away. They seemed to show a government agency, once the object of almost universal respect and awe, reaching out with tentacles to get a grasp on, or lead into, virtually every part of American society.” “In one fell swoop FBI surveillance of dissidents was exposed and the Bureau’s carefully nurtured mystique destroyed,” wrote Max Holland about the Media burglary in his 2012 book Leak: Why Mark Felt Became Deep Throat. “Far from being invincible, the FBI appeared merely petty, obsessed with monitoring what seemed to be, in many cases, lawful dissent.”Historian Richard Gid Powers, in his 2004 book Broken: The Troubled Past and Uncertain Future of the FBI, described the burglary’s impact: Hoover’s power to conduct secret operations . . . depended on the absolute freedom he had won from any inquiry into the internal operations of the Bureau. . . . Except for a remarkably few breaches of security . . . Hoover had been able to pick and choose what the public would learn about the Bureau. He had never suffered the indignity of having an outside, unsympathetic investigator look into what he had been doing, what the Bureau had become, and what it looked like from the inside. And it had been that luxury of freedom that let him indulge himself with such abuses of power as his persecution of King, the . . . COINTELPROs, and his harassment of Bureau critics.On the night of March 8, 1971, that changed forever. A group calling itself the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI broke into the FBI resident agency in Media, Pennsylvania. The burglars were never caught.As two hundred FBI agents searched for the burglars throughout the country in 1971, most intensively in Philadelphia, even people in the large peace movement there, where all of the burglars were activists, could not imagine that any of their fellow activists had had the courage or audacity to burglarize an FBI office. Many people feared then that the FBI might be stifling dissent, but most people found it difficult to imagine that anyone would risk their freedom—-risk sacrificing years away from their children and other loved ones—-to break into an FBI office to get evidence of whether that was true. People wondered: Who would go to prison to save dissent?That question will now be answered. For more than forty years, the Media burglars have been silent about what they did on the night of March 8, 1971. Seven of the eight burglars have been found by this writer, the first journalist to anonymously receive and then write about the files two weeks after the burglary. In the more than forty years since they were among the most hunted people in the country as they eluded FBI agents during the intensive investigation ordered by Hoover, they have lived rather quiet lives as law–abiding, good citizens who moved from youth to middle age and, for some, now to their senior years. They kept the promise they made to one another as they met for the last time immediately before they released copies of the stolen files to the public—-that they would take their secret, the Media burglary, to their graves.The seven burglars who have been found have agreed to break their silence so that the story of their act of resistance that uncovered the secret FBI can be told. Their inside account, as well as the FBI’s account of its search for the burglars—-as told by agents in interviews and as drawn from the 33,698–page official record of the FBI’s investigation of the burglary obtained under the Freedom of Information Act—-and the powerful impact of this historic act of resistance are all told here for the first time. It is a story about the destructive power of excessive government secrecy. It is a story about the potential power of nonviolent resistance, even when used against the most powerful law enforcement agency in the nation. It also is a story about courage and patriotism. |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.