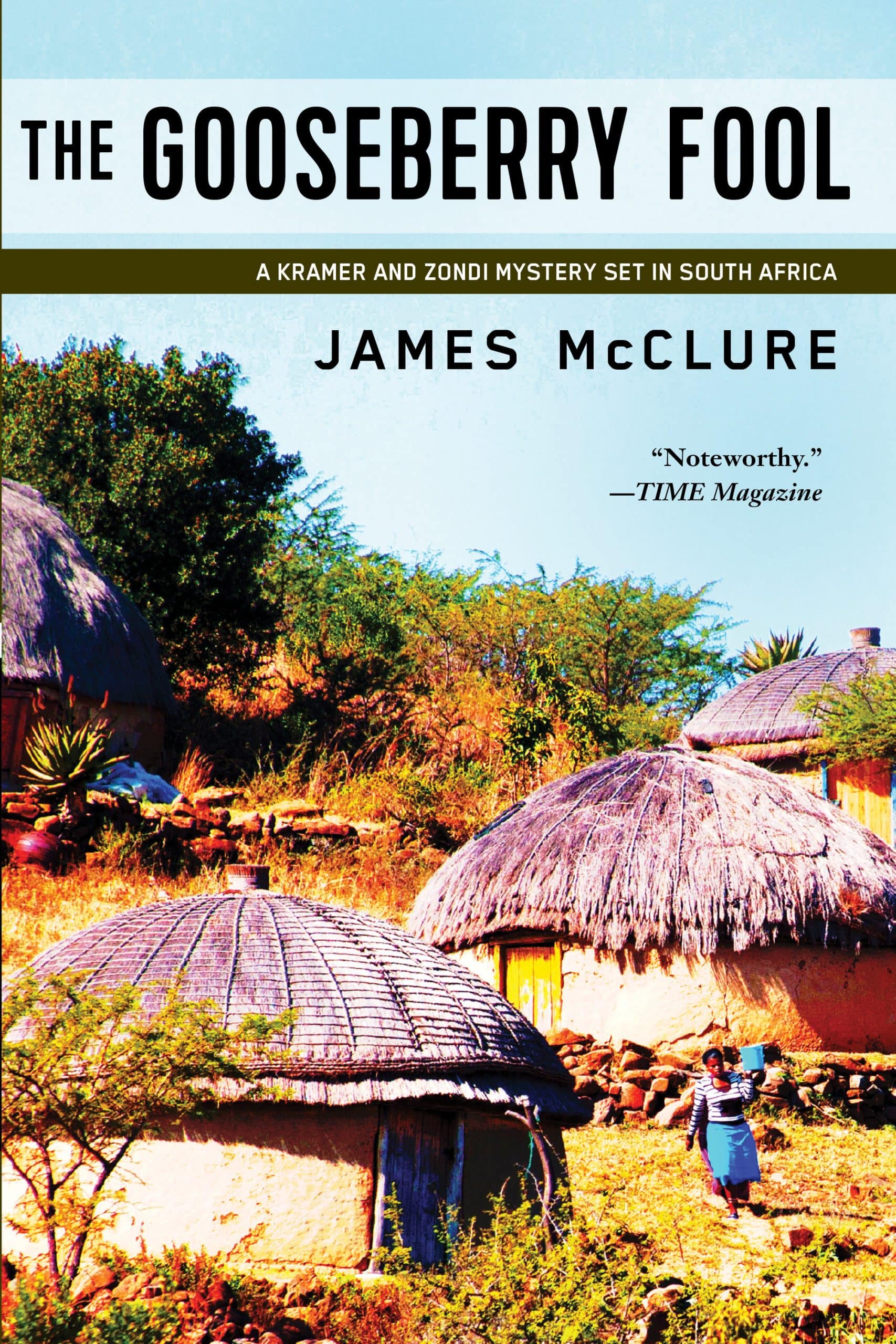

The Gooseberry Fool

14.00 JOD

Please allow 2 – 5 weeks for delivery of this item

Description

Hugo Swart, faithful churchgoer and respected citizen, is found stabbed to death on the floor of his kitchen just before Christmas, on the hottest night of the year. If Mr. Swart’s Reverend is to be believed, no one in the world could have a reason to kill him; the murder was most likely a robbery gone ugly, and the chief suspect is Swart’s black servant, Shabalala, who has fled to the countryside. But Lieutenant Kramer suspects that not everything is as it seems. While Zondi pursues Shabalala in what turns out to be a treacherous tour of miserable outlying Bantu villages, Kramer tries to wring the truth out of some of Swart’s acquaintances in Trekkersburg and Cape Town—it seems not everyone liked the victim quite as much as the Reverend did. But danger lies at every turn—what will this investigation cost the duo?McClure’s merciless depiction of 1970s South Africa, its many layers of racism, and the gaps between rich and poor make this perhaps the most devourable book in the Kramer and Zondi series yet.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.28 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 1.48 × 12.68 × 19.03 cm |

| PubliCanadation City/Country | USA |

| by | |

| Format | Paperback |

| Language | |

| Pages | 240 |

| Publisher | |

| Year Published | 2011-6-14 |

| Imprint | |

| ISBN 10 | 1569479437 |

| About The Author | James McClure (1939-2006) was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he worked as a photographer and then a teacher before becoming a crime reporter. He published eight wildly successful books in the Kramer and Zondi series during his lifetime. The first two books in the series, The Steam Pig and The Caterpillar Cop, are available in paperback from Soho Crime. |

Praise for James McClure:"The pace is fast, the solution ingenious. Above all, however, is the author’s extraordinary naturalistic style. He is that rarity—a sensitive writer who can carry his point without forcing."—The New York Times Book Review “More than a good mystery story, which it is, The Steam Pig is also a revealing picture of the hate and sickness of the apartheid society of South Africa.”—Washington Post “So artfully conceived as to engender cheers…. A memorable mystery.”—Los Angeles Times "Soho completes its reprinting of one of the finest police series to begin in the 1970s, James McClure's eight books about Tromp Kramer and Mickey Zondi, a South African biracial detective team in the days of Apartheid." —Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine“A superior story by any yardstick.”—Portland Oregonian |

|

| Excerpt From Book | 1HUGO SWART ENTERED purgatory just after nine o’clockon the hottest night of the year. It came as a complete surpriseto him, as it did to his several acquaintances, who, knowinghim for a pious young bachelor, were unable to reconcile thiswith the thought of his brutal murder.His surprise, however, was of a different order—owingnothing to assumption and everything to sudden agony as realas the improvised weapon with which it was inflicted. And inhis final flare of consciousness, he acknowledged an inexplicableoversight.This had been to presume that once inside his house, withthe front door bolted and the back door locked, he was alone.He really should have considered the possibility of an intruderstealing in while he was away at Mass. Even just made theroutine check carried out by any householder upon arrivalhome, let alone a man in his circumstances. Then he mighthave noticed a shadow flinch as he tossed his Missal across thedarkened study onto his desk. But he did not. Nor did he actuallygo into the study, pausing only at the door.Instead, with much that was pleasing on his mind, he wentstraight on through to the kitchen, humming to himself. HisAfrican servant had left the light burning in the ceiling andhis dinner burning in the oven. The sharp smell of the ruinedsteak registered immediately, yet the only thought he gave toit was to switch off the stove. Thirst, rather than hunger, washis dominant drive.He opened the refrigerator door and found everything heneeded for a long, very cold drink. Vodka was his choice, forhe believed it left the breath untainted—vodka and orangeand plenty of ice. The simple procedure totally absorbed him.He measured out the spirit first, returning the bottle to itshiding place in the vegetable tray. Next came two fingersof fruit juice from a can, then three ice cubes, and finally atopping of chilled water. Instantly the tall glass frosted overand droplets began to wriggle down its thin sides. For it tobe really cold, however, he had to wait until the ice did alittle of its work.So he turned on the radio over by the kettle and caught thenews bulletin. December 23 had been the hottest day of theyear, according to the South African Weather Bureau, whichwas not news to anyone. But they were right in making theheat wave the first item; there was an undeniable satisfactionin being part of the news oneself for a change, to knowprecisely how severe an ordeal it had been, to feel—howevermodestly—a survivor.On every level, survival was dear to Hugo Swart, as it is toany man who anticipates a bright new future.The idiot kettle began to boil. He thought at first that thesound, an odd wheeze, came from behind him, then noticedthe air shimmering above the spout—it was altogether toohot and humid for steam to show. Of course. The kettleand the radio shared the same wall socket; switching themboth on at once was a mistake he had made many times. Andsure enough, after a moment’s silence, the kettle gurgledand threatened to melt its element if more water was notswiftly added. That damn black baboon never left the thingproperly filled. All it needed, though, was a sharp tug onthe cord.He gave it one and then took off his lightweight jacket,wishing he had done so ten minutes earlier, and dumped it onthe drain-board.By now the main news was over and the regional summaryunder way. It disclosed that the maximum temperaturein Trekkersburg itself had soared to a record 112 degreesFahrenheit.“In the shade,” the announcer added.To which Hugo Swart, impatient with such pedantry,retorted aloud, “Jesus wept!”His last words.He dithered for a moment over his drink, then decided toincrease the pleasure by prolonging the wait.So he refilled the ice tray at the tap and put it back in therefrigerator. He closed the refrigerator door. He opened it andclosed it again, musing. As children, he and his sister had onceargued bitterly over whether the light in their stepmother’sGeneral Electric went out when the door was shut. The inspirationfor this had been the claim of a fanciful friend whoswore that a fairy, a sort of enslaved Jack Frost, lived on theinside, ready to douse the light the instant it was no longerneeded. This was plainly a lot of rubbish, but posed a questionnonetheless. He had held it was only logical that the light shouldgo out, while his sister—who had sweets he wanted to share—perversely challenged him to prove it did not, in fact, stay on.Naturally, he was unable to do this, and ended up paying lipservice to her irrational viewpoint. He knew that the light mustgo out, but it was as pointless an argument as that between anatheist and a priest debating the immortality of the soul: inboth cases, nothing could be satisfactorily settled this side ofthe door.Hugo Swart laughed softly. There was some truth in thistalk of formative years. What he himself had learned was thepractice of adopting whatever belief best served his own endsat any particular time. And it seemed to be working out verysatisfactorily in this particular instance. Yes, sir.His drink was ready. The ice cubes were half their size,and a wet ring was forming on the breakfast table. This hadcertainly been a moment worth waiting for, yet he decided onone further delay: a toast to his benefactors.With the glass raised high, he turned to the window in thehope of seeing himself there in a comically cynical pose againstthe night. Unfortunately, the Venetian blinds were down andhe could see nothing.Even less than he supposed.For, as he brought the lip of the glass to meet his own,somebody struck him from behind with a steak knife. This firstblow caught him on the left shoulder blade, skittered across theflat bone, and snagged between two vertebrae. Such was theviolence of the blow, its force was transmitted to the extremitiesand the glass flew, untouched, from his hand. He saw itshatter and felt the terrible pain.Strangely, he just stood there—hating the thought of waste,wondering what could conceivably be happening to him, notingthat the next program would be a short interlude of chambermusic. It startled him to finally realize there was someone elsein the room, someone who wheezed when he breathed andmust hate him very much.That was his first surprise. There were others.He staggered into a turn, grabbing at a fork that lay atthe place set for his late supper. But he missed and nevergot to identify his assailant either. Before he could raise hisreeling head, he was blind with his own blood—a wild slashwith the knife having opened up the puffiness beneath hiseyebrows.On the cello’s introductory note came the punched stabto the chest that knocked him back against the table. It wasno good; all he could do was allow himself to sprawl ontothe broken glass and try to think of something to say. LikeHail Mary.Then, in the two beats of silence that followed, artfullycontrived by the composer to key listeners for a bright gush ofvital sound, Hugo Swart had his Adam’s apple cored, and bledswiftly to death.Lasting just long enough to hear his hearing aid beingcrushed underfoot—and then to reflect on what a fool hehad been.2LIEUTENANT TROMP KRAMER of the TrekkersburgMurder Squad sat alone in the third-floor lavatory and wonderedif anyone would be giving him a birthday present. He wasstark naked and held in his right hand a crumple of paper.Man, it was hot. So hot it did things to the mind. His ownhad spent the day preoccupied with thoughts chill and sparklingand as far removed from homicide as a swimming pool froman acid bath. It had also evolved some extraordinary theoriesthat had nothing to do with work either; such as a notion thatthe sun, having drawn up close, was watching, like a boy witha magnifying glass, its brightness burn holes in the map. If thiswas not the way it was, it was the way it felt—particularly ina hole like Trekkersburg. Right then he hated the skew hookbehind the door and hated the backs of his knees, which hefound impossible to press against the cool porcelain pedestal.The outer door squeaked open on its spring and slammedback. The tap at the basin was turned on and left to run in thevain hope its tepid flow would give way to cold water. Meanwhile,he of the sanguinary disposition performed an ashesto-ashes routine with what sounded like a gallon of bleachedCoke aimed at the wall.Kramer frowned, displeased by this intrusion on his privacy.He determined not to invite any exchange, not as much as ahearty vulgarity by way of greeting, and remained very still.He was also careful to make no sound. Not even when knucklesrapped perfunctorily at about the height his clothes were hanging.Which was really a pity, because after the door had squeaked andslammed a second time, the lights were switched out.Bugger. Now it was not only bloody hot but pitch bloody darkas well, and that put paid to the reading matter he had broughtwith him. He drew breath sharply. Another mistake, for it waslike inhaling cheroot smoke on a dark night: dry, stifling, andnasty. Ah, well, this was where his self-indulgent little schemesusually landed him—right where he was perched. Back in hisstuffy cupboard of an office, with its tease of a telephone and aqueue of half-wits wanting their noses wiped, the idea of a tripdown the passage had seemed a master stroke of contingencyplanning. For a full ten minutes before leaving his chair, he hadsavored the thought of stripping off and sitting undisturbed,emptying an occasional mugful from the cistern down his frontwhen the mood took him. Yet another ten minutes later, it wasplain this was not to be.Bugger.He stood up, bent over, pushed the paper between his lapelsand into his jacket pocket, then began to dress. The absurdityof convention in such a climate, however temporarily extreme,was stressed once more as the warmth of his shirt, slacks, andsocks, imperceptible on a winter’s morning, engulfed him.His shoes, which had wandered off behind the brush container,seemed damp within and his toes enjoyed this. But his purpletie tightened like a tourniquet.Done. The tedium of life—and death, for that matter—could begin again. With a pull on the chain for appearances’sake, an old habit he had never been able to lack, he unboltedthe door and felt his way out into the passage—catchingColonel Muller with his finger on the light switch.“Still here, Kramer?”“Sir.”“Excitement too much for you, hey?”“Always is, sir. But I’m on my way right now, never worry.”“Kramer.”“Sir?”“You’re the one with the worries. I’m off to the Free Stateover Christmas, and your old mate Colonel Du Plessis is takingcharge.”Kramer mouthed a short word.“Just what I had in mind,” said the Colonel, grinning, as hedisappeared through the door.Like the good little Kaffir he was, Bantu Detective SergeantMickey Zondi had the Chevrolet waiting, its passenger door hangingopen, right outside the main entrance to the CID building.“You’re bloody keen,” grunted Kramer, sliding in besidehim. How the hell Zondi managed to stay alive in that buttoned-up suit was more than he could imagine, wog or no wog.It must have been ten degrees hotter in there. Still, it did a lotfor his image.Zondi smiled, licking away a sting of saltiness from his upperlip. His expression was parboiled boredom, his face bright withsweat streaks. He started the engine, then teased the car againstthe hand brake. He needed directions.“The note I had said the address was 40-something SunderlandAvenue,” Kramer responded, digging into his jacketpocket. “No time to read it properly. That’s right, 44.”It takes a lot to make tires screech on soft asphalt, but Zondiachieved this with a U-turn only he saw happen. In seconds, airwas rushing in through the side vents so fast Kramer’s eyeballsdried up.He blinked casually and said, “I get the free funeral, you madbastard. Remember that.”“Better,” sighed Zondi, easing off for the traffic lights ahead.He stuck his right hand out of the window to funnel the falsebreeze up his sleeve.“The note,” Kramer began, his tone didactic, “the note saysthat the deceased is one Hugo Swart, aged thirty-three, a bachelor.He lived alone, worked for the provincial administrationas a draftsman, and was a big churchgoer.”Zondi clicked his tongue.“Multiple stab wounds—can mean anything. Last seen aliveeight-thirty.”“By, boss?”“By his priest, Father Lawrence, leaving the church.Same priest discovered the body when he came round aboutnine-thirty to discuss something or other. Steak knife; nofingerprints.”“Where was this body?”“In the kitchen. Don’t ask me how the priest got in. I don’tknow yet.”“Boss Swart was a Catholic? The Roman Danger?”“Not everybody’s Dutch Reformed who’s got an Afrikanername, man.”Zondi gave Kramer an impertinent sideways look and,fending the half punch neatly, took off on a show of green. Hismaster was, at most, nonconforming agnostic.“Any suspects, boss?”“Local station say it must have been a Bantu intruder. Theywould; their bloody answer to everything. But I suppose they couldbe right. When last did anything really happen in this dump?”“When the elephants lived here, I think.”“Too right. Stop if you see a tearoom that’s open.”There was a late-night cafe a few blocks farther on, andKramer had him buy them each an ice lollipop.“I’ll have the chocolate one,” he said, when Zondi got backinto the car. “Can’t have you turning into a bloody cannibalor something.”These delicacies went down very well, lasting all the wayout of the city, across the national road, and into the southernsuburb of Skaapvlei. They ditched the sticks as SunderlandAvenue, lined by the ubiquitous jacaranda tree, twitched offto the left.Just the name of the street would have been enough. Zondihad no need to check the house numbers; the address theysought was clearly indicated by an assortment of vehicles,ranging from the District Surgeon’s Pontiac down to themortuary van and two bicycles, parked haphazardly outside.There was also a crowd of servants on the far pavement,whispering and giggling behind cupped hands—and a fewwhites who had suddenly decided to walk the dog themselves.Things that only happen in films get all the extrasthey can use.Before the Chevrolet had completely stopped, Kramer wasout and standing, thumbs hooked in hip pockets, looking thecrowd over. He was careful how he did it, as somebody theremight have something useful to say. Later on, that was. Firsthe had to inspect the scene of the crime itself and get his bearings.So Kramer swiveled around to take in what the exteriorof number 44 had to offer, nodding to Zondi to proceed as hedid so.The bungalow was the runt in a long line of handsomehouses. Each of them had been born of a separate, consciousact of creation—of that blessed union between boom wealthand architectural talent which, because money is a dominategene, invariably produces a brainchild as individual as itssire. That there were duplications of basic styles—Spanishcolonial, early Cape Dutch, Californian aerodynamic, andrestaurant Tudor—only went to show that nobody is quitethe individual he believes himself to be. There was, however,nothing of the single-litter look of a speculator’s estate aboutthem, even where the bungalow was concerned. Doubtlessits stunted growth had been the result of some nasty frightduring gestation, perhaps a bull running wild in the stockexchange. Poor little sod, for it was plain that, had it risenanother floor, then its roof would not have seemed so unnaturallylarge, nor its truncated Doric pilasters so stumpy. Howout of place it must have felt, and yet quite unable to mix inany other company.As a choice of abode, the bungalow was something else—unusual, to say the least, for a single man, and a humble civilservant at that, Kramer expected the first stirrings within himof interest in the case. None occurred.He walked over to the other side of the road and stopped.Instead there was this awareness that in some strange wayhe despised himself. Despised himself as he would a jadedDon Juan moving compulsively toward another whorehouse,another stranger’s body, another act of professional intimacy,another striving to climax and release, all without feeling athing. Not a damn thing. Just feeding a lust, then walking awayagain. Back past the loungers waiting outside, ready to grabyou, eager to know what you knew and what you had done,too afraid to do it themselves, yet yearning. And how weary abugger felt even before it began. |

| Series |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.