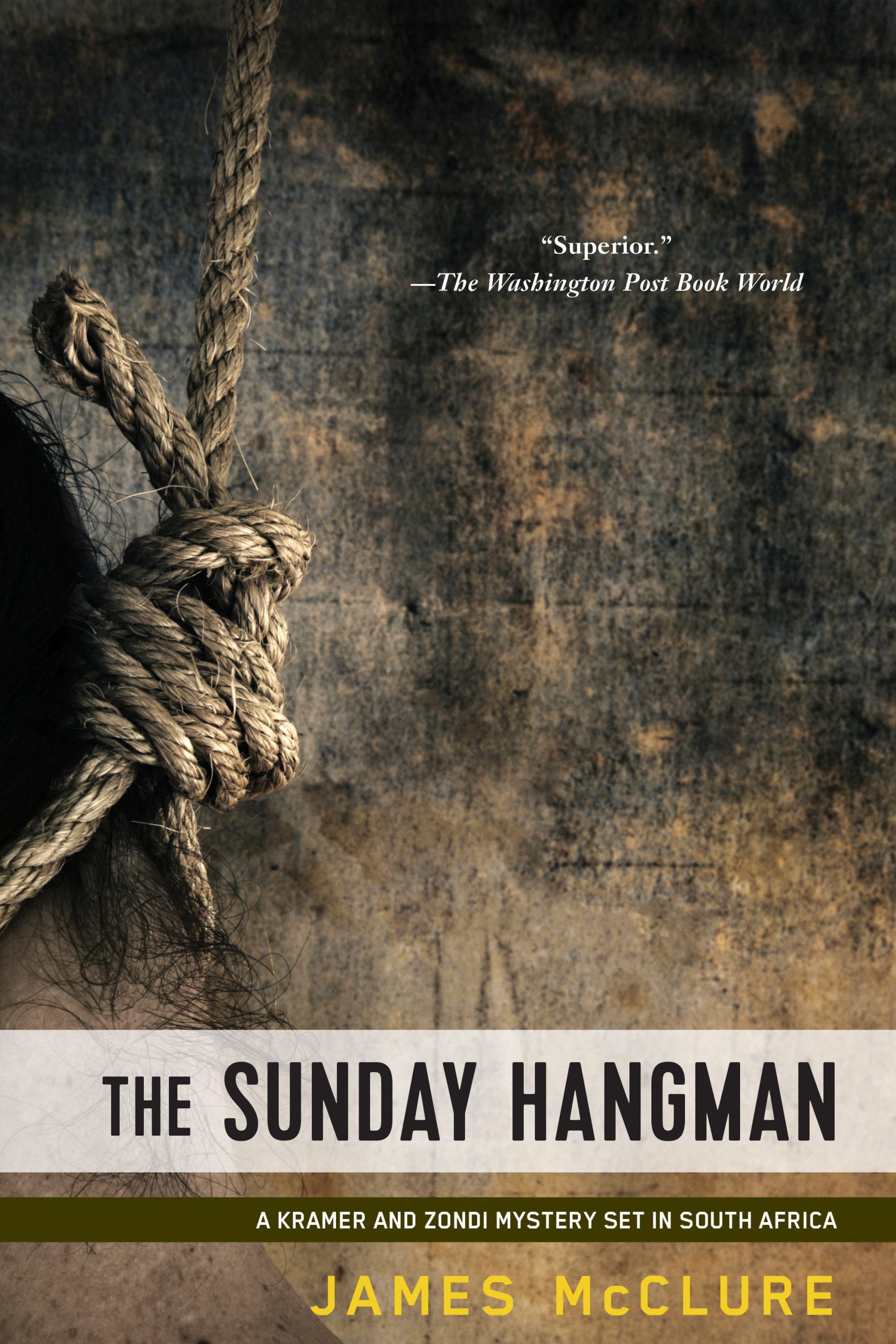

The Sunday Hangman

14.00 JOD

Please allow 2 – 5 weeks for delivery of this item

Add to Gift RegistryDescription

Tollie Erasmus, an unsavory bank robber on the run, is hung from the neck until dead. Unfortunately, execution was administered without the benefit of South African judge or jury. Somewhere there’s a killer who knows far too much about the hangman’s craft, and Lieutenant Tromp Kramer and his Bantu assistant Mickey Zondi must find him before his trail of death continues.

Additional information

| Weight | 1.69 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 1.78 × 12.73 × 19.5 cm |

| PubliCanadation City/Country | USA |

| Format | |

| language1 | |

| Pages | 284 |

| Publisher | |

| Year Published | 2012-2-7 |

| Imprint | |

| ISBN 10 | 1616951052 |

| About The Author | James McClure (1939-2006) was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he worked as a photographer and then a teacher before becoming a crime reporter. He published eight wildly successful books in the Kramer and Zondi series during his lifetime and was the recipient of the CWA Silver and Gold Daggers. |

Praise for James McClure: "The pace is fast, the solution ingenious. Above all, however, is the author’s extraordinary naturalistic style. He is that rarity—a sensitive writer who can carry his point without forcing."—The New York Times Book Review “More than a good mystery story, which it is, The Steam Pig is also a revealing picture of the hate and sickness of the apartheid society of South Africa.”—Washington Post “So artfully conceived as to engender cheers…. A memorable mystery.”—Los Angeles Times “This well-plotted, well-written murder mystery is exceptional … sometimes grim, sometimes sourly comic, always shocking.”—The Atlantic“Probably one of the best police procedurals published so far in 2012.” —Mystery Tribune"Soho completes its reprinting of one of the finest police series to begin in the 1970s, James McClure's eight books about Tromp Kramer and Mickey Zondi, a South African biracial detective team in the days of Apartheid."—Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine |

|

| Excerpt From Book | 1Tollie Erasmus looked at the room in which hewas about to die, and saw there the story of his life. Nothinghad ever turned out quite the way he’d imagined it. For once, however, he was very relieved to find this was so.In nightmare after nightmare, he had seen himself in a harshlylit execution chamber that had whitewashed walls and highfanlights, a scrubbed wooden floor and a crude beam, a longlever and a thick, bloodstained rope. Whereas, in fact, thechamber was far more like a hospital corner, screened off bygreen curtaining and lit by a warm orange glow; there was aclinical sparkle to the brass pulley, and the rope was so cleanit must have been specially sterilized, assuring him of a swift,certain, scientifically humane end to his days. Tollie was thinking very fast, absorbing all this in a twinklingwhile, on another level, wondering what had happened toall the in-between bits. He couldn’t remember his arrest, thetrial, or the passing of sentence. It was like coming round ina dentist’s chair: you knew where you were and why, but youdidn’t want to probe too much for fear of the onrush of pain. His other senses were recovering now. He smelled theprison stink of disinfectant and tasted brandy. In his left handwas something squarish. His hand wasn’t visible. None of himwas visible. He had been rolled up in a sheet so expertly hecouldn’t move. A sheet wrapped round and round and round,and pinned neatly down the side with safety pins. He was sittingin a chair, bound to it by a wide, soft bandage that wentround and round and round. This couldn’t be right. Think, Tollie, think fast. The shape of the room was wrong. Every weekday morningat Pretoria Central he’d waited in the soccer yard to be marchedoff to the workshops with the others. Facing him, as he stoodthere, had been two and a half stories of solid wall with onlya fanlight near the top. If you didn’t guess right away that thiswas the gallows building, you soon enough learned, becauseon Tuesdays and Thursdays there was often a delay while theyfinished nailing down the coffin lids. Inevitably, you came toknow its dimensions pretty well, and this room just didn’t gowith them at all. Think faster. The pulley for only one rope was another thing—and so wasthe amount of floor space. He knew for a fact that sometimesthey strung up six kaffirs at once, and no way could six standside by side on that area of trap door. Naturally, the wardersliked to exaggerate the figures they dealt with, but he had seenthe evidence of a multiple hanging with his own eyes. Afterleaving the soccer yard, you went up some steps at the side ofthe gallows building and along a passage between the door tothe laying-out room and the door they brought them out of,over sawdust sprinkled to keep the drips of blood from stickingto your feet. And one Thursday morning, after an unusuallylong delay, he had actually seen six pairs of soggy khaki shortsbeing dropped outside the door for collection by the laundry.He recalled the warder winking at him, and wiping a hand onthe wall. He had ears as well. He couldn’t hear the sound that neverceased within the walls of Central—except, very abruptly,when the traps went down: the sound of the kaffir condemnedssinging hymns and chanting in the great cell in B2. They alwayssang even louder before a hanging, making “Abide with Me”last all night, driving A and B sections crazy, which served theprivileged bastards right. Although even in C, which was thatmuch farther away, they got to you when the lights came onat five-thirty and there was that final upsurge before the long,empty silence. Fighting to impose his sanity on an insane situation, Tollieput a simple question to himself: If I’m not in Central, thenwhere the sod am I? It wasn’t a dream, and logically he couldn’t be anywhereelse, despite all the— Tollie knew exactly where he was, and just why thingshadn’t matched up to his experience. He had been away fromCentral a good while, and had forgotten the new buildingfor the condemneds which had been going up on the rise justbehind it. A really modern place, the papers had said, withall sorts of up-to-date ideas; the inmates had nicknamed itBeverly Hills. In that same instant, everything slotted into place. The ideaof having one gallows for all races had always surprised him;this was the gallows reserved for whites, which explained thecurtains and the single rope. The constant hymn-singing fromB2, back in the old block, had worked on everyone’s nerves;now, the kaffirs had been put in a new section that was sensiblysoundproofed. As for the sheet around him, it was animprovement on the old straight jacket, which, as the wardershad often complained, had never worked all that well on thereally stroppy cases. Having resolved the immediate conflicts set up by his awakeningin a room like that, Tollie suddenly realized he’d neverhad a mental blackout before. In fact, he could remember quitedistinctly— “Don’t be frightened, son, you won’t feel any pain,” said adeep voice behind him. “We’re all here and it’s half-past fiveon the dot.”2In his time, Lieutenant Tromp Kramer of the TrekkersburgMurder and Robbery Squad had been asked to believemany things. But when they told him that Tollie Erasmus hadhanged himself, he simply shook his head. “See for yourself,” said the new man in Fingerprints, dealinghim a photograph from the batch in his hand. “I took that myselfthis morning, as you can tell from how nice and clear it is.”Kramer used an apathetic finger to bring the picture roundthe right way up on the bar counter. Sure enough, that was theface of Tollie Erasmus, all right: a sleekly handsome, pointyface, with small, close-set eyes; the sort of face a bull terrierwould have if it were human. A dead face, moreover, and therewas a rope around the neck. “Where?” he murmured, glancing up to see who else hadcome across to the hotel from police headquarters opposite.He really should have guessed. Why, it was none otherthan Sergeant Klip Marais, the gladdest bearer of ill tidings inthe Criminal Investigation Department, and, an obsequious,sometimes quarrelsome, little runt to boot. “Lieut Gardiner said to inform you immediately,” explainedMarais, his tone repenting the levity shown by his companion.“We saw the note you had left in your office for Zondi, andso. . . .” “Where?” Kramer repeated. “Ach, upcountry,” said the new man. “They had him unidentifiedat Doringboom, and the Lieut sent me to get prints, etcetera. Then, when I got back just now, the other blokes all recognizedhim straight off, and I was sent to find you in CID.” He seemed amused by his present surroundings. “So Doringboom is handling this?” Kramer said, pocketingthe print. “When are they doing the P.M.?” “This afternoon, I hear.” “Uh huh. The body was found when?” “Today.” “Where?” “In one of those picnic places for cars alongside the nationalroad, about twenty kilometers this side of Doringboom. Hiscar was there also, a green Ford, and he’d strung himself upon a thorn tree just by the fence. Some umfaans made a reportto a family that had stopped for breakfast with their caravan.He hadn’t been there all that long; only a few hours—or that’swhat the doc says.” “Doc who?” “Don’t ask me—the local district surgeon, whoever he is.” “Uh huh.” Kramer stared at this new man, and then decided that he wasnot going to be an asset to crime detection in the division. Shynessmade some people cocky, and so did being the minimumrequired height of five foot six, but here was an object thatwas neither of those things: if anything, he was almost as tallas Kramer himself, a lot bulkier, and his swagger showed evenin the way his greasy quiff was combed back. It was curious how the unbelievable had this effect, temptingyou into thinking about petty irrelevancies, while, deep inside,certain adjustments were made. “Are you offering?” the new man asked, nodding at the drinkin front of Kramer. “Why not?” “Um—I think I’d best be getting back,” said Marais, edgingaway. “Um—see you, hey?” They watched him go. “By the way, I’m Klaas Havenga,” the oaf announced, snappinghis fingers for the Indian barman. “A brandy and orange,no ice, and the officer here is paying for it.” “The same,” Kramer added, noting how automatic hisresponses had become. He took out the picture for another look at it. “So what’s this all about?” Havenga asked, after using hisfirst sip as a mouth rinse. “Marais was trying to tell me as wecame across, but you know how that bugger talks, nineteen tothe dozen like a bloody coolie.” The barman, a sensitive soul, moved to the far end of thecounter, taking his newspaper with him. He’d been writingsome interesting names into the crossword when the two jokershad arrived, armed with their bombshell. “I was looking for him,” said Kramer, feeling nothing as yet. “Oh, ja? Is it true he tried to take a pot shot at you once,only your boy went and buggered things up?” “Three months ago,” Kramer replied, taking some icefrom the plastic barrel. “We got a late tip-off there could be araid up on that rise in Peacevale where there’s a line of Bantubusiness premises—ach, you know, along that dirt road thatruns parallel to the dual carriageway. They were trying outthe idea of a small bank there at the time. Right on noon, ourinformant said, but when we rolled up, the bloody thing wasalready in progress.” “Yirra!” “Not that it looked like it. The people outside didn’t evenknow at that particular moment, he was so quick. They wereused to seeing armed whites going in, carrying the bank’smoney—and the same went for the bank employees. The stupidbastards took him right up to the safe and opened it. Anyway,Erasmus comes running out with his gun up before we realizedthe position. Mine was still in under here, so Zondi spinsthe car around, to give me time to draw. As he comes on toErasmus’s side, he gets a thirty-eight in the leg, straight throughthe bloody door. That was it.” “How do you mean?” asked Havenga, frowning. “The leg went stiff, onto the accelerator, and we went intothe front of this fruit shop—glass, grapes, cabbages everywhere.The owner was killed outright.” Never, so it seemed, had the man heard anything funnier.Kramer smiled indulgently as he came up for air. “Jesus Christ! C-c-cabbages everywhere!” Havenga gasped,rejoicing in such a vision. “Man, you’ll have to excuse me a sec.” And he used the back of his inky hand to smear the tearsfrom his eyes, before beckoning for the barman. “Same again,” he ordered. “Only this time I pay.” “Like hell,” said Kramer, and the matter rested there. While the barman saw to their refills, a bright splash ofreflected light began to flutter across the bottles and glasseson the shelves behind the counter. “Who’s doing that?” muttered some old bugger irritably,following its progress back and forth. Nobody could answer him, so he slid off his stool and wentover to the mullioned windows behind them, which gave thebar its spurious look of a Tudor tavern. But the frosted panesdefeated his attempts to peer through, and he went out ontothe pavement to do some shouting. “So go on,” Havenga invited Kramer, clinking glasses.“While your boy was making a damn fool of you in all thosegrapes and bloody mangoes, Tollie got clean away?” “Uh huh.” “This is the first time you’ve heard of him since?” “The first. His home town was Durban, but he didn’t goback there. We’ve had a running check going in all the bigcenters—Joey’s, Cape Town, P.E.—without any joy so far.What plates did he have on his car?” But Havenga was distracted at that moment by the returnof the old misery from the pavement. “Who was it?” asked a visiting farmer, who’d apparentlyordered them both fresh lagers in the meantime. “Some kidleft in—” “No, some insolent little black bastard, waggling his tobaccotin or something about over the other side, just grinned atme—you know the type. Dressed up like a dog’s dinner in abloody suit he must have swiped. I don’t know. This for me?Very good of you, old chap.” “If you like, I’ll go and kick his backside,” the farmer offered,being a much younger man. “No, no; I’ve sent him packing! Best of health!”Havenga grinned cynically and turned back to Kramer. “Sorry, what was that?” “I asked you about his sodding plates.” “Ach, I never saw them. Don’t these bloody English killyou?” The splash of light crossed Havenga’s face even as he spoke,slipping from it to move like a butterfly from the Oude Meesterbrandy over to the till. “What’s he playing at?” exploded the old man, banging downhis tankard. “Just who the devil does he think he is?” Suddenly Kramer came to, and realized he knew the probableanswers to both those questions. Not only this, but thathe’d now made his adjustments, and the time had come toact. “Duty calls?” asked Havenga, puzzled to see him rise sopurposefully for no obvious reason. “Duty, Sergeant? I came off duty officially at six o’clock thismorning.” “But I . . . you mean, Marais. . . ?” And the new man in Fingerprints looked at the glass in hishand, before coming the old comrade with a slightly uneasylaugh: “You aren’t going to report me, hey, sir?” “Naturally,” said Kramer, just for the hell of it.Over on the other side of the street, just as he’d supposed,leaned the jaunty figure of Bantu Detective Sergeant MickeyZondi, still overcoming his problem of access to the bar withthe aid of a spare 9mm magazine, angled to catch the sun. Aninstant later, however, this had stopped, and the fly little sodwas on his way across. “How goes it, Mickey?” “Not so good, boss—and not so bad. I was two hours withMama Makitini, but she swears to God she never had one dropof that vodka in her shebeen. Then, by chance, I find Yankee BoyMsomi round the back of Pillay’s place, and I get a tip for us towatch where the Mpendu brothers go tonight, because maybethere is a connection. I am sorry you had to wait so long.” “That’s okay; just got a bloody gutsful of the office. I’vebeen talking.” “Who with? The old guy with the fine command of the Zululanguage?” Zondi joked, waving a shaky fist. “Only it would bea kindness to explain to him the difference between bhema andbhepa. He crudely told me to go and smoke myself.” “Hmmm.” “Boss?” asked Zondi, quick to match moods. “Forget the bloody vodka and the Mpendus. I’m going tohave a word with the Colonel, while you get the car filled up.Be in the yard at one.” “Where do we go?” “Doringboom. A post-mortem in Doringboom.” “Hau! This is a murder inquiry?” “Well, at the moment,” Kramer said, “that seems to be amatter of opinion. Here, you tell me what you think.” He handed over the photograph. Zondi’s fleeting scowl was involuntary. He returned thepicture, gave no sign of what was going through his head, andtook a step away. “I get the car, boss.” “Fine.” Kramer set off in the opposite direction, heading for theCID building, then side-stepped into the shadow of an offloadingCoke truck. That limp wasn’t getting any better; infact, when Zondi thought you weren’t looking, it tended to become a lot worse. |

| series |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.