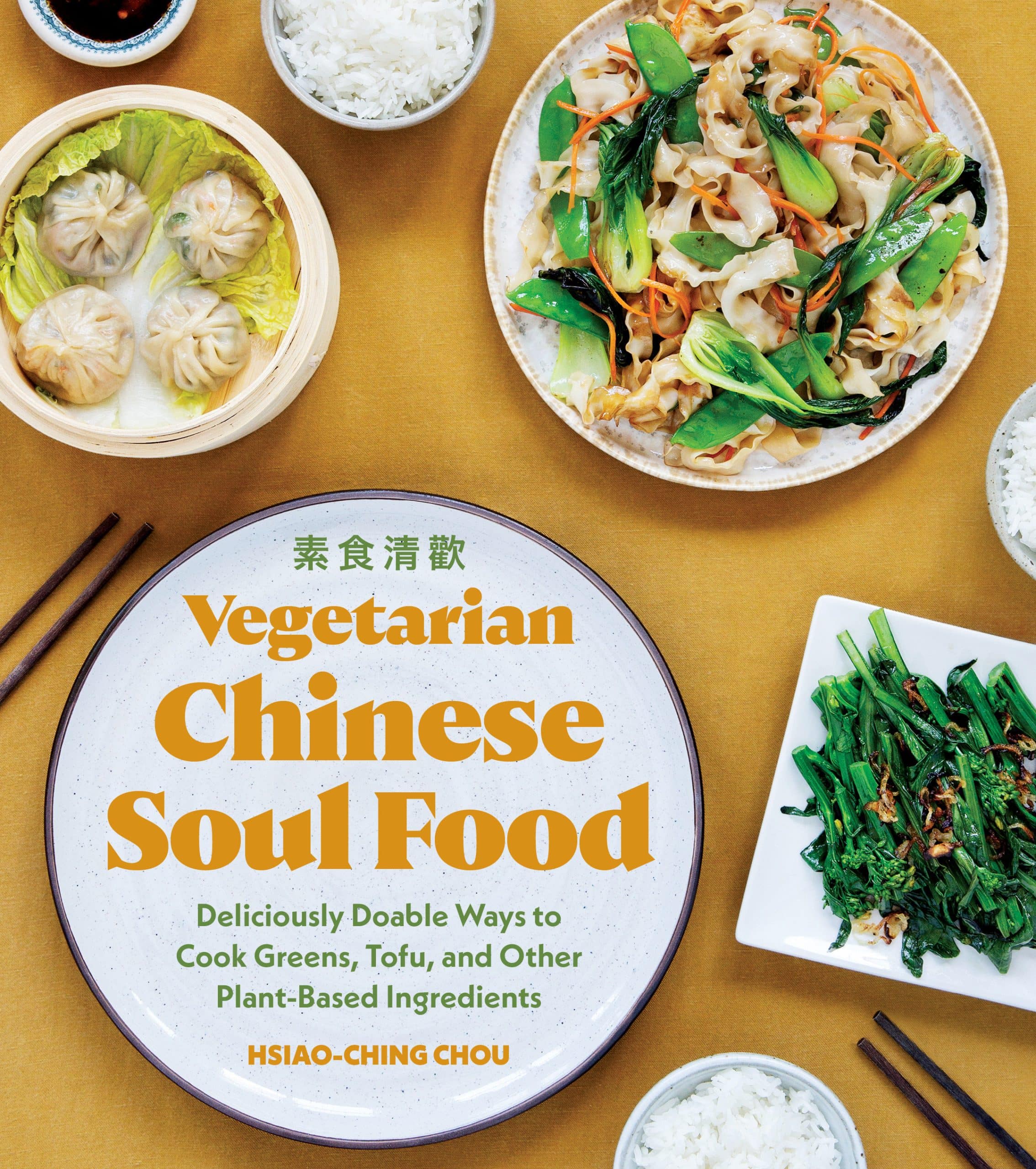

Vegetarian Chinese Soul Food: Deliciously Doable Ways to Cook Greens, Tofu, and Other Plant-Based Ingredients

18.00 JOD

Please allow 2 – 5 weeks for delivery of this item

Add to Gift RegistryDescription

Learn to make vegetarian Chinese food with 75 soulful, plant-based recipes even the most basic cooks can make at home! Chinese Soul Food drew cooks into the kitchen with the assurance they could make Chinese cuisine at home. Author Hsiao-Ching Chou’s friendly and accessible recipes work for everyone—including average home cooks. In this new collection, you’ll find 75 vegetarian recipes divided into 9 chapters:• Dumplings—Chou’s specialty! • Dim Sum and Small Bites • Soups and Braises • Steamed Dishes • Rice and Noodles such as • Tofu • Eggs • Salads and Pickles You’ll also find helpful information on essential equipment, core Chinese pantry ingredients (with acceptable substitutions), how to season and maintain a wok, and other practical tips. Whether you’re a vegetarian or simply reducing the amount of meat in your daily diet, these foolproof Chinese comfort food recipes can be prepared any night of the week. As the author likes to say . . . any kitchen can be a Chinese kitchen!

Additional information

| Weight | 0.79 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 1.53 × 20.32 × 22.86 cm |

| PubliCanadation City/Country | USA |

| Author(s) | |

| Format Old` | |

| language1 | |

| Pages | 272 |

| Publisher | |

| Year Published | 2022-4-26 |

| Imprint | |

| ISBN 10 | 1632174545 |

| About The Author | Hsiao-Ching Chou is an award-winning food journalist, a cooking instructor, and communications consultant. She is a member of the James Beard Foundation cookbook committee and Les Dames d'Escoffier. Chou has been a guest on local and national shows, including Public Radio's The Splendid Table, the PBS documentary The Meaning of Food, and the Travel Channel's Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations. In her spare time, she teaches popular everyday Chinese home cooking classes at the Hot Stove Society. She lives with her family in Seattle. |

Named One of Delish's 10 Best Cookbooks of 2021"[Hsiao-Ching Chou's] sole regret about her first cookbook, [Chinese Soul Food], is that she didn’t include more vegetarian recipes. Her second one—Vegetarian Chinese Soul Food—comes right when we could use more vegetables after overdoing the COVID-19 stay-home holidays. [Chou] concentrates on accessible assistance: mostly straightforward recipes, wok-buying advice, a guide to pantry ingredients, a vegetable tutorial and more."—Seattle Times"Hsiao-Ching Chou’s new cookbook is an exercise in exceptional approachability."—Seattle Met magazine"In this compact book Hsiao-Ching Chou, a Seattle-area cooking instructor who’s particularly popular for her dumpling classes, demonstrates the astonishing diversity and appeal of Chinese vegetarian cooking."—Kitchen Arts & Letters"Above all, Vegetarian Chinese Soul Food is another example of the author’s passion for sharing China’s storied cuisine. She’s committed to encouraging people to try their hands at creating exciting home-cooked meals that will leave them satisfied and perhaps a little surprised at their own abilities. Once again Chou proves that any kitchen can be a Chinese kitchen—even a vegetarian one."—International Examiner"The beauty of [this] cookbook, and Chinese cooking in general, is that it’s forgiving."—Pittsburgh Post-Gazette |

|

| Excerpt From Book | Vegetables are essential in Chinese cooking. Whether a mound of stir-fried greens,a burbling clay pot of tofu and cabbage, or a side of spicy pickles, vegetable dishesare put together with as much thought as any meat or seafood dish. Balance ofseasonality, flavors, textures, and sometimes curative properties guides the preparation.Even those who eat meat are biased toward having an abundance of vegetables.Many dishes include meat only as an accompaniment.Being vegetarian in the Chinese culture is not perceived as a character flaw. Notonly is vegetarianism accepted, but the industry for producing plant-based productsand meat substitutes has a long history. That is due in large part to ChineseBuddhist monks and nuns who adhere to a vegan diet that also excludes pungentingredients, such as alcohol, garlic, onions, leeks, and chives. Not all followers ofBuddhism subscribe to a vegetarian diet, however. But temple vegetarian cuisineis well known and even revered. Culturally, meat has always been considered aluxury because it’s expensive. During Lunar New Year, serving a broad selection ofmeats and seafood represents wealth, abundance, and good fortune. Historically,the advent of meat and seafood substitutes made from plant-based ingredientshas meant that those who couldn’t afford meat or those who have chosen to bevegetarian for health or religious reasons could also share in the symbolism, especiallywhen it comes to “lucky foods” served during the Lunar New Year reunionfeast. Using bean curd and wheat gluten to create meat substitutes goes back toimperial China and has been around for over a thousand years.I have noticed recently at the Chinese market where I shop here in the Seattlearea that there are more products marketed toward vegetarians. For example, thesame hoisin sauce that I’ve always used now has a bottle label listing it as vegetarian.It’s the same naturally vegetarian sauce, just a different label. My motherand I scrutinized the label and finally surmised that the “vegetarian” designationpotentially has to do with the fact that “hoisin” is hai xian in Mandarin, whichmeans “seafood,” and adding the word “vegetarian” was a clear message that thehai xian sauce does not contain seafood. Likewise, a bottle of Chinese black vinegarhad a sitting Buddha figure on its label that also proclaimed that the vinegar isvegetarian. Again, we suspect it’s a direct way to signal to vegetarians, especiallyBuddhist vegetarians, that this vinegar is not flavored with any forbidden pungentingredients.For me, a meal is never complete without at least one vegetable dish. My producedrawers are always stocked with Chinese cabbage, baby bok choy, gai lan(Chinese broccoli), Chinese mustard greens, yu choy, and a revolving cast of otherfamiliar vegetables—carrots, celery, kale, lettuce, cucumber, broccoli, cauliflower,potatoes, and such—that cater to our cravings. At a moment’s notice—or in thetime it takes to make a pot of rice—I can have a sumptuous meal on the table withplatters of greens, eggplant, mushrooms, and tofu. Delicate, hearty, savory, pungent,and crunchy all coexist in their individuality and intersections.The diversity of vegetables and plant foods is dizzying. On occasion, I teachan Asian greens cooking class, where I display a dozen kinds of uncooked leafygreens paired with their respective stir-fried versions. Students then sample eachvegetable, and the deliciousness is always a revelation. I will never not delight inthe looks on people’s faces when they taste discovery.In the Chinese language, the word for “vegetables” is cai (also spelled tsai, choy,or choi). It’s a broad term that covers a world of greens as a category, as well as thespecific members of this succulent family: bok choy, yu choy, gai choy, qincai, ongchoy, and so on. Cai is also a general term for “dish”—as in “What dishes should weeat today?” or “What dishes should I cook today?”I love the preciseness and expansiveness of the term cai: It means one thing andeverything, so context is important for determining whether you’re referring to aspecific vegetable or a meal. If you’re not used to such conciseness in language, itmay cause confusion. To me, there’s freedom in this ability to shapeshift, which wecertainly can extend to the versatility of the Chinese way with all forms of vegetablesand plant foods.When I talk about a way with vegetables, my intention is to convey an approachrather than rigid rules and recipes. The alchemy of a searing wok, a splash of oil, amess of fresh greens, and a dash of soy sauce delivers a quintessential flavor thatroots your palate in this approach. From that point of reference, a kaleidoscope ofdazzling combinations can emerge at the twist of inspiration. A recipe with specificamounts isn’t as important as understanding the nature of vegetables and thesupport characters that make them sing.As I’ve become more attuned to the wisdom that comes from lived experiences,I have realized that my taste preferences have shed thrill-seeking for more focusedflavors. I do enjoy adding a dollop of fire from my menagerie of chili sauces to manydishes, but I also understand the value of restraint. I will always encourage youto experiment with building complexity in your cooking, and I will also alwaysremind you to appreciate the elemental. Subtle flavors in food are not boring.The way to cook vegetables, for me, is about exploring flavors without heroicsat the stove. I remain firm in my belief that everyday cooking should be accessibleand forgiving. As with this book’s predecessor, my goal is to ground you in everydayChinese home cooking, with hopes you will consider developing your ownChinese kitchen. |

| series |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.